Heart rate variability in athletes has gained significant attention as a crucial indicator of physical fitness and recovery. This metric reflects the body’s ability to adapt to stress and is particularly valuable for monitoring the training and performance of athletes. Analyzing the HRV of athletes, coaches, and trainers can gain insights into an athlete’s autonomic nervous system activity, recovery status, and overall well-being. Understanding heart rate variability (HRV) helps optimize training loads and plays a vital role in preventing overtraining and injuries. In this article, we will explore the importance of HRV in athletes, its impact on performance, and how it can be effectively utilized to enhance athletic outcomes.

Table of Contents

Toggle- Athletes’ Pursuit of Improvement and the Role of HRV

- HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES DURING AND AFTER EXERCISE (INDICATORS OF STRESS/TRAINING LOAD)

- THE USE OF HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES: OVERTRAINING AND HOW AVOID IT?

- LIMITATIONS, IMPROVEMENTS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES OF ANALYSIS OF HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES PERFORMANCE

- THE GOAL OF MONITORING OF HRV IN ATHLETES PERFORMANCE

- BioSignals 5: A Comprehensive Biofeedback Tool for Precision HRV Training

- How Can Biofeedback Data Be Used To Plan Optimal Athletic Training?

- HeartMath Inner Balance: Cultivating Recovery and Nervous System Balance

- FAQ: HRV in Athletes

Athletes’ Pursuit of Improvement and the Role of HRV

As an athlete, you always look for that 1% improvement in every aspect of your game. However, as elite athletes improve and the margin for improvement narrows, achieving a 1% improvement becomes harder. With that in mind, athletes are conditioned to revert to the “train harder” mentality to grab that 1%. This mentality doesn’t always work because, much too often, overtraining and injuries occur. If you want to ensure your body is peaking at the right moments, having insight into HRV is the coveted 1% that all athletes are looking for.

Heart rate variability (HRV) represents variations between consecutive heartbeats (beat-to-beat or R-R interval) over time. This beat-to-beat variation in heart rhythm is considered normal and even desirable. When variations between consecutive heartbeats disappear, autonomic dysfunction is often the cause. This dysfunction can link to neurological, cardiovascular, and psychiatric diseases. Many studies show that greater heart rate variability is associated with reduced mortality, improved quality of life, and enhanced physical fitness. (Learn more about Heart Rate Variability here).

Physiological Background and HRV’s Impact on Athletes’ Performance

The physiological background of HRV is complex and affected by circulating hormones, baroreceptors, chemoreceptors, and muscle afferents. An important factor influencing HRV is respiratory sinus arrhythmia – the natural variation in heart rate (HR) during breathing. During inspiration, HR increases, whereas during expiration, HR decreases. The autonomic nervous system (ANS), through sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) pathways, regulates the function of internal organs and the cardiovascular system. During training or competition, sympathetic activity (“fight or flight”) increases an athlete’s cardiac contractility, heart rate, breathing, and muscle tension.

In contrast, parasympathetic (vagal) stimulation (“rest and digest”) reduces an athlete’s heart rate, relaxes muscles, and allows for digestion. Any source of stress (psychological, physical, or illness-related) will provoke disturbance of the ANS and, consequently, of HRV. The long-term imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic tones can impair athletes’ performance.

HRV data offers a unique view into nervous system activity. This insight helps athletes find the right balance between training and recovery.

HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES DURING AND AFTER EXERCISE (INDICATORS OF STRESS/TRAINING LOAD)

During exercise, HRV is reduced (shorter R-R intervals), and heart rate is increased due to augmented SNS and attenuated PNS activity. Not only are the intervals between R-R peaks shorter, but they also become more uniform (reduced R-R variability).

The relationship between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity during exercise depends directly on training intensity. During physical activity, sympathetic nerves can increase cardiac output to 2 to 3 times the resting value.

Caution should be taken when interpreting HRV analysis during exercise. When exercise intensity exceeds 90% of VO2 max, breathing frequency rises. This increase boosts vagal contribution, or PNS activity, due purely to the heart’s mechanical properties rather than any neural input from the ANS. As a result, PNS activity, driven by faster respiration, can mask actual SNS activity at these higher intensities. To ensure accurate results, the athlete should maintain a stable respiration rate as much as possible during an incremental test to exhaustion.

TRAINING LOAD

The distribution of training loads is a fundamental component of periodization. The elements that comprise the training load are training volume and intensity. The interplay between these two elements will define the total training load. Higher training loads will cause greater ANS disturbance and sympathovagal imbalance. Post-exercise HRV analysis appears to be a valuable indicator of performance variations and can indirectly reflect training load. There is evidence that HRV parameters are highly correlated with the intensity and volume of exercise and are inversely related to training load.

RECOVERY AND HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES PERFORMANCE

Understanding Stress, Adaptation, and Recovery in Training

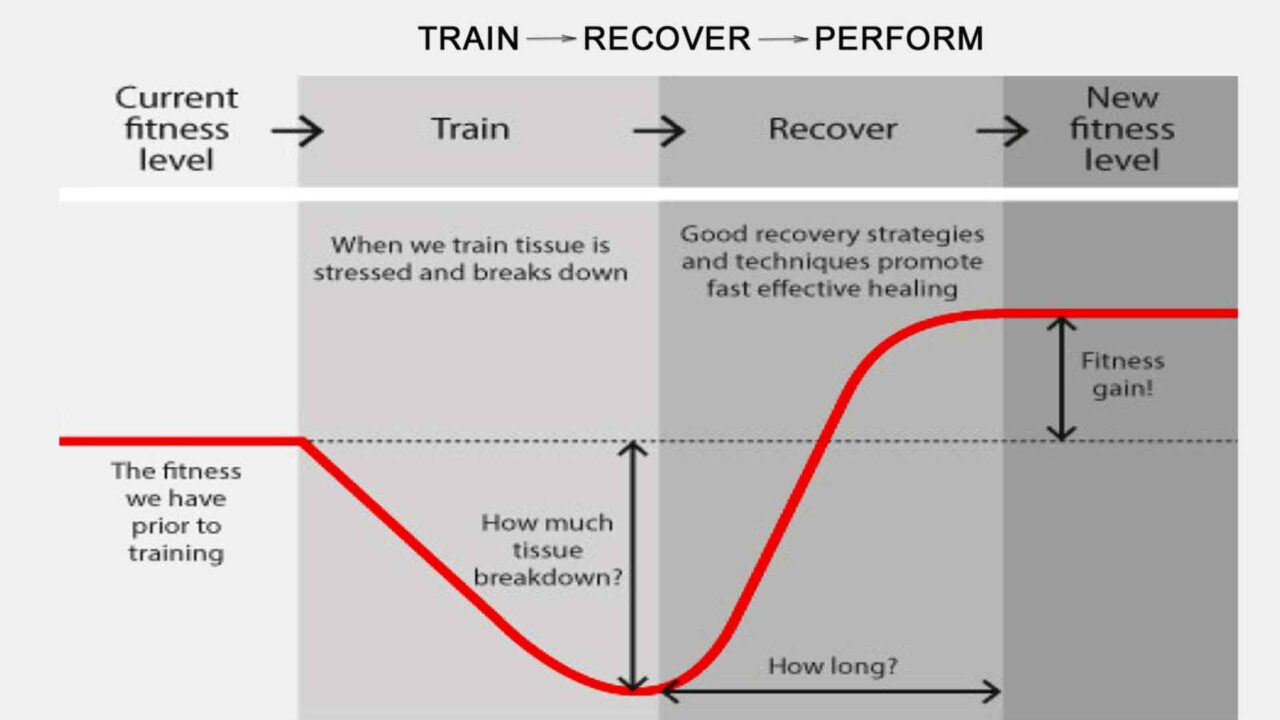

On the assumption that physical activity causes stress (a stimulus), the body will respond with a stress reaction on different physiological levels. In addition to a stress reaction, adaptation processes occur during recovery. Suppose the magnitude of the stress stimulus (training load) is high enough (overload principle) to evoke a reaction in the body. In that case, the response will be proportional to the stress level, and, as a result, greater training effects (adaptation) will be achieved.

To achieve higher performance levels in sports, it is essential to understand that well-designed, integrated rest periods are crucial. Recovery after training is considered an integral part of the training methodology. Performance will not improve without optimal recovery. Problems occur when the demands are so frequent that the body cannot adapt. This means the body will remain continuously under sympathetic dominance during rest and activity.

Most athletes and sports science personnel understand the importance of recovery after exercise, defined as the return of the body to homeostasis after training to pre-training or near-pre-training levels.

The Role of Recovery and Its Impact on Performance

Recovery involves getting adequate rest between training sessions/competitions to allow the body to repair and strengthen itself in preparation for the subsequent bout. Optimal athletic performance is supported when recovery to pre-training or near pre-training levels is permitted. If recovery is insufficient, hindrance of physiological adaptation and reduced athletic performance should be expected. Recovery plays a significant role in minimizing the harmful effects of training (fatigue) while retaining the positive impact (improved fitness/strength/performance).

Without monitoring recovery after exercise, fatigue can build up and become excessive before competition. This buildup reduces athletic performance and may even lead to overtraining syndrome. Overtraining syndrome occurs when training stress is too high and recovery is insufficient, leading to fatigue and decreased performance.

Every training session stresses the body and disturbs homeostasis and ANS modulation. These changes in ANS activity manifest as increased sympathetic or decreased parasympathetic activity, reflected in HRV parameters. One crucial aspect of recovery is sleep, during which parasympathetic activity should dominate. However, an optimal recovery state typically features parasympathetic (vagal) predominance of the ANS, regardless of the time of day.

HRV as a Noninvasive Tool for Monitoring Recovery

Various parameters can be used to measure post-exercise recovery (VO2 max, creatine kinase, C-reactive protein, plasma cortisol, blood leukocyte, myeloperoxidase protein level, and glutathione status). However, these methods are mostly invasive, time-consuming, and expensive for everyday use. Accordingly, the importance of a noninvasive, easy, and affordable method to evaluate recovery is evident. Thus, HRV technology is increasingly used to assess the status and level of recovery.

Long-term high-intensity training sessions gradually decrease the parasympathetic component of HRV, which increases during the rest of the period. The sympathetic component demonstrates the opposite tendency.

Reactivating HRV’s parasympathetic activity to pre-exercise levels as quickly as possible significantly improves athletes’ recovery. When HRV parameters cannot return to pre-exercise or optimal levels within a reasonable time, this indicates a chronic disturbance in ANS activity. Such a disturbance can lead to overtraining.

Today, HRV-based devices and software support recovery analysis, providing easily interpretable data for trainers and athletes. The most common procedure to evaluate recovery level involves overnight (nocturnal) HRV measurement, although systems that can assess a quick recovery index (5-minute measurement) are also available.

THE USE OF HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES: OVERTRAINING AND HOW AVOID IT?

Sometimes, the line between optimal performance level and overtraining is skinny.

Overtraining syndrome (OTS) results from a long-term imbalance between stress (internal and external) and recovery periods. A large body of evidence suggests that overtraining syndrome leads to a significant imbalance in cardiac autonomic function between the two ANS pathways (sympathetic and parasympathetic).

The literature contains conflicting results about ANS modulation in overtrained athletes. Some studies report a predominance of sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic tone during an overtrained period. The description of different types of overtraining might explain these disputed results.

Two types of OTS have been reported: sympathetic and parasympathetic overtraining, each with specific physiological characteristics.

Sympathetic tone

Insomnia

Irritability

Tachycardia

Agitation

Hypertension

Restlessness

Parasympathetic tone

Fatigue

Bradycardia

Depression

Loss of motivation

The early stages of performance impairment feature sympathetic domination of the ANS at rest. This condition is often called an “overreaching state” or “short-term overtraining.” This means that the disturbance of homeostasis was neither severe nor prolonged enough to provoke a chronic overtraining state. Therefore, the time required to recover all physiological systems fully typically spans several days to weeks.

Sports that require higher exercise intensity generally show increased sympathetic tone. If the overreaching state (sympathetic autonomic tone domination) persists, OTS and parasympathetic autonomic tone domination will develop. Parasympathetic OTS dominates in sports characterized by high training volume.

LIMITATIONS, IMPROVEMENTS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES OF ANALYSIS OF HEART RATE VARIABILITY IN ATHLETES PERFORMANCE

Analysis of heart rate variability in athletes’ performance has become a widely accepted method for noninvasive evaluation of ANS modulation during and after exercise. To overcome the disadvantages above, the recording signal must contain at least 5 minutes of HRV fluctuations to obtain reliable results.

In the last 5 years, the number of devices and software programs/apps using HRV technology has increased exponentially. The current trend in software engineering is to make all wireless sensors for capturing and transmitting HRV data compatible with smartphones. Hardware and software engineers are continuously improving the accuracy of sensors that record and receive HRV signals (heart rate belts, wireless technologies, and protocols) and HRV analysis techniques (software, mathematical models). This provides the trainer and athlete with quick and easy analysis of HRV data during and after a training workout (training load, recovery, and overtraining).

THE GOAL OF MONITORING OF HRV IN ATHLETES PERFORMANCE

HRV provides an excellent objective status of the autonomic nervous system. The primary goal is to reduce injuries, decrease overreaching, improve player health, increase adaptation, and enhance learning through training. However, winning requires that talent is available and optimized in performance, not just uninjured. The essence of monitoring heart rate variability in athletes is to establish a routine and accountability process for achieving success. The data collected from HRV can guide athletes like a compass to a training program blueprint, but only if there is a commitment from everyone. Winning requires talent and preparation, and while only a few can be at the top of the mountain, HRV can increase those odds if used appropriately.

MEASUREMENT PROTOCOL

Metrics

- RMSSD is the most commonly used and trusted metric. It is a clear marker of parasympathetic activity (recovery). RMSSD is linked to changes in performance, fatigue states, overreaching, and overtraining. The return of RMSSD to baseline after exercise has been associated with the clearance of plasma catecholamines, lactate, and other metabolic byproducts, as well as the restoration of fluid balance and body temperature.

Therefore, RMSSD serves as a global marker of homeostasis, reflecting various aspects of recovery. This marker may explain why planning intense training when HRV is at or above baseline can help improve endurance performance. - Duration: 60 seconds to 2 minutes in the morning is the ideal measurement protocol for reliability and practical applicability in team settings. Night measurements are also a valid method.

- Frequency: To establish a valid baseline, at least three days per week are required. More measurements can be beneficial, ideally up to five. If compliance is an issue, prioritize the three days in the middle of the week, far from matches, to avoid residual fatigue.

Data analysis: The most critical parameters to examine are baseline HRV and the coefficient of variation (CV).

- HRV baseline: computed as the average HRV over a week (or 3-5 days if daily measurements are challenging to obtain). An athlete’s average values should be analyzed. Typical values are a statistical representation of historical data collected over the previous 30 to 60 days. This should give us insights into where we expect the HRV baseline to be, provided no significant stressors are present. In cases of substantial stressors or issues in responding to training or lifestyle stressors, the baseline will deviate from typical values.

- CV: Coefficient of Variation, or the amount of day-to-day variability in HRV.

Insights

Pre-session: load can be adjusted based on individual responses, as shown in baseline HRV and CV. In particular:

- Athletes showing a reduced HRV and increased CV most likely struggle with the load and might benefit from reduced load or other recovery strategies (sleep, diet, yoga, or different ways to minimize non-training-related stress, for example).

- Athletes showing a stable or increasing HRV are likely coping well with the increased load.

- Athletes showing a reduced CV likely cope well with the increased load unless their baseline HRV reduces or goes below average. In this case, the reduced CV might highlight an inability to respond to training.

The same patterns throughout the session can help you understand individual responses to changes in training load. Use HRV as a continuous feedback loop rather than a target to optimize toward a specific value. Staff working with athletes and physiological measures should prioritize baseline and CV changes to determine individual responses and adaptations.

HRV ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AND PRACTICAL RECOMMENDATION

- HRV is an indication of your resilience – the ability of the nervous system to respond and recover from physical or psychological stressors;

- HRV values depend on the length of the measurement

– 5 minutes = short term HRV

– 24 hours = long term HRV; - HRV is age and gender-dependent.

- HRV has a circadian rhythm;

- HRV may change day to day with your biorhythm or due to emotional or physical stress;

- HRV is dependent on body position;

- Chronic low HRV is an indication of systemic health (psychological or physical) issues;

- HRV measurement should be provided for the same length of time each day (3 minutes typical);

- HRV should be taken at the same time each day

– First thing in the morning is recommended - HRV should be taken in the same position

– Lying down

– Sitting

– Standing

BioSignals 5: A Comprehensive Biofeedback Tool for Precision HRV Training

From Elite Secret to Accessible, Multi-Parameter Data

Historically, precise HRV analysis required clinical-grade equipment. The BioSignals 5 biofeedback sensor makes this level of detail accessible, providing multiple HRV indices, such as RMSSD and SDNN, alongside simultaneous breathing biofeedback. This multi-parameter approach offers a comprehensive view of autonomic nervous system activity for athletes and coaches.

Precision Metrics for Informed Decisions

The BioSignals App delivers detailed, real-time data. A key metric is the Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD), a primary time-domain measure that best reflects parasympathetic “rest and digest” activity. Accurate RMSSD measurements can be taken in 60 seconds or less, providing a quick and reliable snapshot of recovery status. The ability to monitor breathing patterns concurrently with HRV adds a critical layer of insight, as respiratory sinus arrhythmia is a fundamental component of HRV.

How Can Biofeedback Data Be Used To Plan Optimal Athletic Training?

The power of the BioSignals 5 sensors biofeedback device comes from establishing a personal HRV baseline. An athlete takes a daily reading upon waking for one week. The average of these measurements—particularly for a key metric like RMSSD—establishes a baseline.

This baseline then guides daily training:

- If morning readings fall below the baseline, it signals incomplete recovery, suggesting a need to ease off on training.

- If readings are at or above the baseline, it indicates full recovery and readiness for a challenging workout.

Data-Driven Training Decisions

HRV measurements from the BioSignals 5 give athletes an objective method to determine when to rest and when to push harder. This data-driven approach helps prevent overtraining and undertraining by moving beyond subjective feeling to quantifiable physiological readiness.

HeartMath Inner Balance: Cultivating Recovery and Nervous System Balance

The Role of Coherence in Recovery

While detailed HRV metrics are crucial, the goal of recovery is a balanced autonomic nervous system with vigorous parasympathetic activity. The HeartMath Inner Balance sensor is specifically designed to cultivate this state. It focuses on achieving heart coherence—a smooth, ordered heart rhythm pattern that reduces stress and enhances the body’s regenerative processes.

HRV as A Noninvasive Tool For Monitoring Recovery

Reactivating the parasympathetic nervous system after training is vital. The HeartMath Inner Balance offers a practical, non-invasive tool for this purpose. Through guided breathing exercises and real-time feedback, it directly trains the user to shift into a physiologically coherent and recovered state. This practice helps accelerate the return to parasympathetic dominance, a cornerstone of effective recovery.

A Practical Tool to Avoid Overtraining

Overtraining syndrome stems from a long-term imbalance between stress and recovery. The HeartMath Inner Balance helps athletes manage this balance by providing a tangible method to reduce sympathetic overdrive (stress) and promote psychological and physiological calm. Regular use fosters resilience, helping to mitigate the irritability, restlessness, and agitation associated with the sympathetic overtraining state.

FAQ: HRV in Athletes

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) measures the variation in time between your heartbeats. For athletes, a higher HRV generally indicates a well-recovered body and a resilient nervous system, which is crucial for optimal performance, preventing overtraining, and guiding daily training intensity.

HRV acts as an early warning system. If your HRV is consistently lower than your baseline, it signals that your body is under-recovered and stressed. This allows you to reduce training load before full-blown overtraining syndrome, characterized by fatigue and decreased performance, sets in.

RMSSD is the most commonly used and trusted HRV metric for athletes. It is a clear marker of parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) activity and serves as a global indicator of recovery, reflecting the body’s return to homeostasis after training.

A low HRV indicates that the sympathetic (stress) nervous system is dominant, meaning the body is under-recovered from physical, psychological, or lifestyle stressors. This state increases the risk of injury and performance decline if intense training continues.

Yes, absolutely. The speed at which your HRV returns to its pre-exercise baseline is a key indicator of recovery efficiency. A slow return suggests incomplete recovery and chronic ANS disturbance, which can lead to overtraining.

HRV biofeedback devices, like those mentioned in the document, train you to consciously increase your HRV by guiding your breathing. This practice enhances your ability to shift into a recovered, parasympathetic state, accelerating recovery and improving nervous system resilience.

Add a Comment