Anxiety disorders are some of the most prevalent mental health challenges, often severely impacting a person’s ability to live a fulfilling life. Neurofeedback for anxiety offers a natural and effective approach to managing these disorders by reshaping and rewiring brain activity rather than simply masking symptoms. As one of the best treatment methods, neurofeedback therapy for anxiety, this method helps individuals gain long-term control over their mental health. If you’re seeking the best neurofeedback device for anxiety, you can find options designed to support your journey to a calmer, more balanced mind.

Table of Contents

Toggle- Symptoms of Anxiety Disorders

- Types of Anxiety Disorders

- Other Conditions Where Anxiety is Present

- Anxiety Disorder Risk Factors

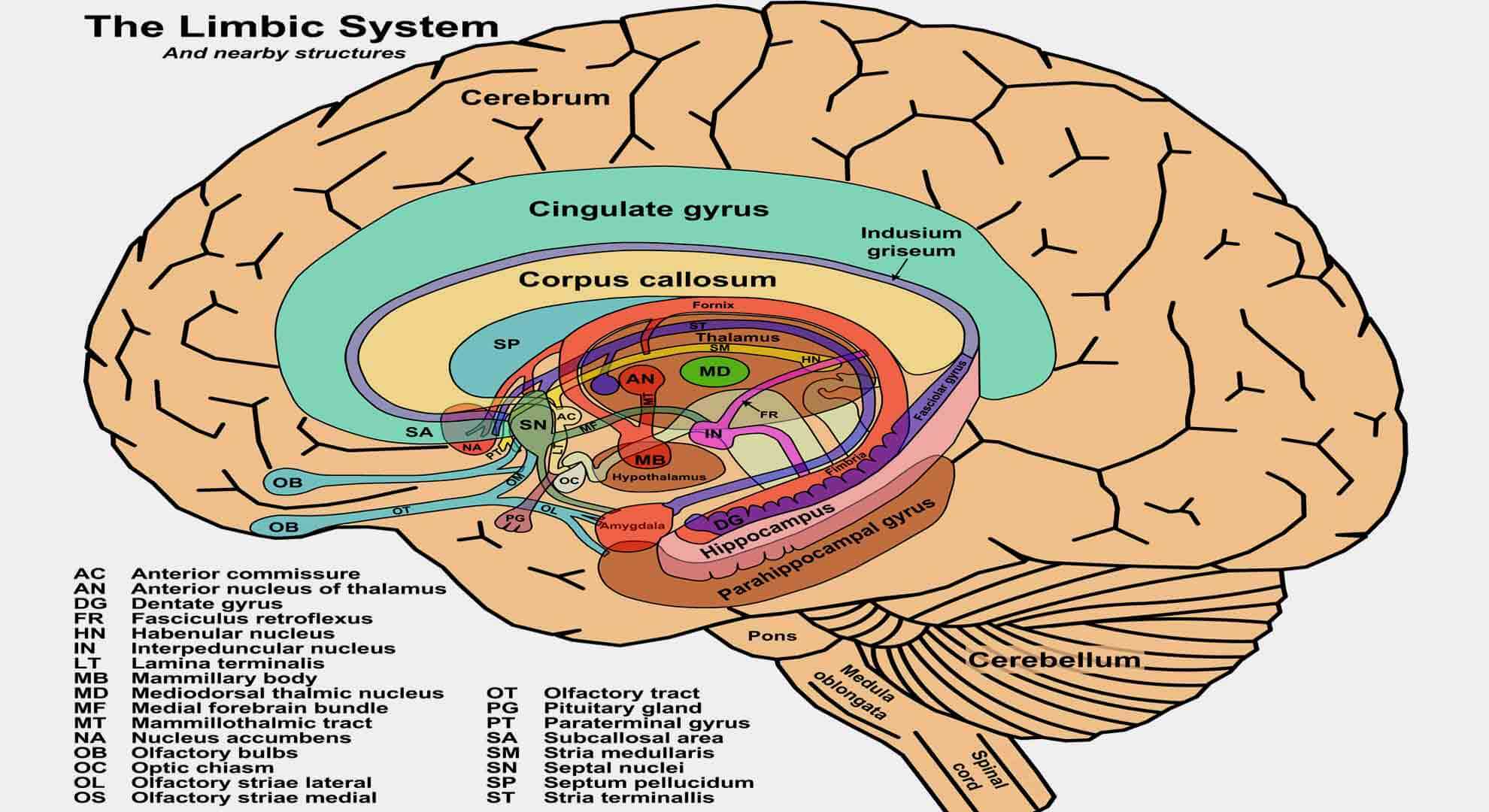

- Brain Region and Anxiety Disorders from Neurofeedback Management Perspective

- The Role of the Frontal Cortex in Emotion and Anxiety Regulation

- The Limbic Cortex: Its Role in Anxiety and Emotional Processing

- The Hippocampus: Its Role in Stress, Memory, and Anxiety Disorders

- Fear and Anxiety: The Amygdala’s Role in Emotional Responses

- Brain Structure and Neurotransmitter Imbalances in Anxiety Disorders

- Neurofeedback for Anxiety Disorders

- Understanding Anxiety’s Impact on Health

- Anxiety in Children and Traditional Treatment Approaches

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety

- Neurofeedback vs. Medication for Anxiety Disorders

- How Neurofeedback Works for Anxiety Management

- Targeting Specific Brainwaves in Neurofeedback for Anxiety

- Neurofeedback Protocols and Long-Term Anxiety Management

- How Neurofeedback Training Reduces Anxiety and Enhances Brain Function

- Best Neurofeedback Device for Anxiety Management at Home

- FAQ: Neurofeedback for Anxiety

Anxiety is a normal and often healthy emotion. Anxiety is a natural human reaction that involves the mind and body. It serves a crucial, essential survival function. Anxiety is an alarm system that is activated whenever a person perceives a danger or threat. When a person feels threatened, under pressure, or facing a stressful situation, the body responds with the fight-or-flight response. Because anxiety makes a person alert, focused, and ready to head off potential problems, a little anxiety can help us do our best in situations that involve performance and motivation to solve problems.

But anxiety that’s too strong and long-lasting can interfere with doing our best. Too much anxiety can cause people to feel overwhelmed, tongue-tied, or unable to do what they need to do. When a person regularly feels disproportionate levels of anxiety, then it is likely to cross the line from normal anxiety into the territory of an anxiety disorder, and it might become a medical disorder. Anxiety Disorders are among the most common mental health issues and can be disabling, preventing a person from living the life that they want. But the good thing is that Anxiety Disorders are highly treatable. Neurofeedback for anxiety disorder management is very effective, with long-lasting results.

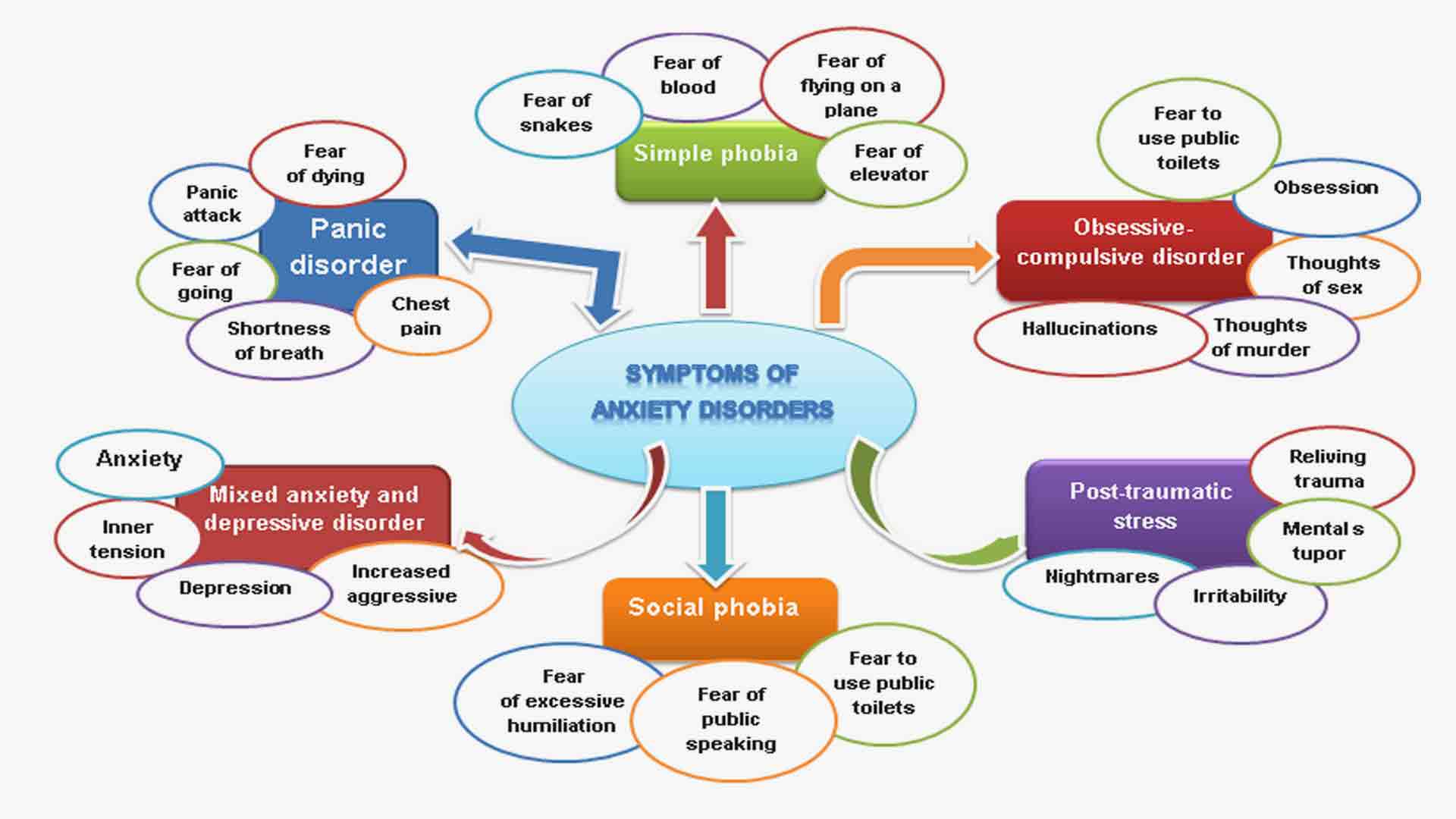

Symptoms of Anxiety Disorders

To treat anxiety, it is necessary to recognize the symptoms and manifestations promptly. The symptoms may not resolve on their own; if left untreated, they can begin to take over a person’s life. It’s essential to seek support early if you’re experiencing anxiety.

Anxiety disorders are often a group of related conditions, and symptoms may vary from person to person. One person can get panicky at the thought of some problem; others may struggle with a disabling fear or uncontrollable, intrusive thoughts, and someone else may suffer from intense anxiety attacks that strike without warning. Yet another may live in constant tension, worrying about anything and everything. But despite their different forms, all anxiety disorders illicit an intense fear or worry out of proportion to the situation at hand.

The symptoms of anxiety disorder often include the following:

- restlessness, and a feeling of being “on edge”;

- uncontrollable feelings of worry;

- increased irritability;

- concentration difficulties;

- sleep difficulties, such as problems in falling or staying asleep.

In addition to the primary symptom of excessive and irrational fear and worry, other common emotional symptoms of an anxiety disorder include:

- Feelings of apprehension or dread;

- Watching for signs of danger;

- Anticipating the worst;

- Trouble concentrating;

- Feeling tense and jumpy;

- Irritability;

- Feeling like your mind’s gone blank.

But anxiety is more than just a feeling. As a product of the body’s fight-or-flight response, anxiety also involves a wide range of physical symptoms, including:

Because of these physical symptoms, anxiety sufferers often mistake their disorder for a medical illness. They may visit many doctors and make numerous trips to the hospital before their anxiety disorder is finally recognized.

Types of Anxiety Disorders

There are different types of anxiety. The most common is the following.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

A person feels anxious most days, worrying about many different things for six months or more.

Suppose constant worries and fears distract a person from his day-to-day activities, or he is troubled by a persistent feeling that something terrible will happen. In that case, this person may be suffering from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). People with GAD are chronic worrywarts who feel anxious nearly all of the time, though they may not even know why.

Anxiety related to GAD often manifests in physical symptoms like chest pain, headache, tiredness, tight muscles, insomnia, stomach upset or vomiting, restlessness, and fatigue. Generalized anxiety can lead a person to miss school or avoid social activities. With generalized anxiety, worries can feel like a burden, making life feel overwhelming or out of control.

Social Anxiety Disorder

A person with a social anxiety disorder has an intense fear of being viewed negatively by others, being criticized, embarrassed, or humiliated, even in everyday situations, such as speaking publicly, eating in public, being assertive at work, or making small talk. It is also known as social phobia.

Social anxiety disorder can be thought of as extreme shyness. In severe cases, individuals avoid social situations altogether. Performance anxiety is the most common type of social phobia.

Phobias and Irrational Fears

A person with a phobia feels an unrealistic or exaggerated fear of a particular object, activity, or situation that, in reality, presents little to no danger. He may go to great lengths to avoid the object of fear, but unfortunately, avoidance only strengthens the phobia.

There are many different types of phobias. Common phobias include a fear of animals (such as snakes and spiders), a fear of flying, and a fear of heights.

Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder

A person has panic attacks, which are intense, overwhelming, and often uncontrollable feelings of anxiety combined with a range of physical symptoms. Someone having a panic attack may experience shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, and excessive perspiration. Sometimes, people experiencing a panic attack think they are having a heart attack or are about to die.

If a person has recurrent panic attacks or persistent fears for more than a month, they’re said to have panic disorder. Panic disorder is characterized by repeated, unexpected panic attacks, as well as fear of experiencing another episode. Agoraphobia is an intense fear of panic attacks that causes a person to avoid going anywhere where a panic attack could occur.

Other Conditions Where Anxiety is Present

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

A person has ongoing unwanted/intrusive thoughts and fears that cause anxiety and seem impossible to stop or control. Although people may acknowledge these thoughts as silly, they often try to relieve stress by carrying out certain behaviors or rituals.

For a person with OCD, anxiety takes the form of obsessions (evil thoughts) and compulsions (actions that try to relieve anxiety). For example, a fear of germs and contamination can lead to constantly washing hands and clothes.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can happen after a person experiences a traumatic or life-threatening event (e.g., war, assault, accident, disaster). Symptoms of PTSD can include difficulty relaxing, nightmares or flashbacks of the event, hypervigilance, startling easily, withdrawing from others, and avoidance of anything related to the event. PTSD is diagnosed when a person has symptoms for at least a month.

Separation Anxiety Disorder

While separation anxiety is a normal stage of development, if anxieties intensify or are persistent enough to get in the way of school or other activities, your child may have a separation anxiety disorder. Children with a separation anxiety disorder may become agitated at just the thought of being away from mom or dad and complain of sickness to avoid playing with friends or going to school.

Anxiety Disorder Risk Factors

Researchers are finding that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the risk of developing an anxiety disorder. Although the risk factors for each type of anxiety disorder can vary, some general risk factors for all kinds of anxiety disorders include:

- Temperamental traits of shyness or behavioral inhibition in childhood;

- Exposure to stressful and negative life or environmental events in early childhood or adulthood;

- A history of anxiety or other mental illnesses in biological relatives;

- Some physical health conditions, such as thyroid problems, heart arrhythmias, or caffeine or other

substances/medications can produce or aggravate anxiety symptoms. - Inflammation affects subcortical and cortical brain circuits associated with motivation, motor activity, and cortical brain regions associated with arousal, anxiety, and alarm.

There is a surprising specificity in the impact of inflammation on behavior. Researches show that inflammation not only occurs in depression but also in multiple other psychiatric diseases, including anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, and schizophrenia. These data suggest that inflammation is transdiagnostic in nature, occurring in subpopulations of patients with several psychiatric disorders. It is revealed that Yoga and alpha meditation increase parasympathetic outflow and consequently decrease inflammation.

A physical health examination is helpful in the evaluation of a possible anxiety disorder.

Self Test for Anxiety

This Self-Assessment Test for Anxiety is called the General Anxiety Disorder screening tool with seven questions (GAD-7). It can help you find out if you might have an anxiety disorder that needs treatment. It calculates how many common symptoms you have and, based on your answers, suggests where you might be on a scale from mild to severe anxiety.

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) for Rating by Clinicians

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) was one of the first rating scales developed to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms. It is still widely used today in clinical and research settings. The scale is intended for adults, adolescents, and children and should take approximately ten to fifteen minutes to administer.

The central value of HAM-A is to assess the patient’s response to a course of treatment rather than as a diagnostic or screening tool. By administering the scale serially, a clinician can document the results of drug treatment, psychotherapy, or neurofeedback.

The scale consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms, and measures both psychic anxiety (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety).

Brain Region and Anxiety Disorders from Neurofeedback Management Perspective

Typically, the brain manages our fear and anxiety without allowing them to interfere with our daily functioning. If there’s a nearby threat, different brain areas help us make sense of the danger by amplifying or quelling our anxiety and fear.

The various anxiety disorders involve many different areas of the brain. These areas reflect both the uniqueness of each of these disorders and the features that they have in common. Anxiety is the result of interaction between several different brain regions — a fear network. No one brain region drives anxiety on its own. Instead, interactions among many brain areas are critical for how we experience anxiety. Contemporary models of anxiety disorders have primarily focused on amygdala-cortical interactions. We only feel anxiety when signals from the amygdala overpower the cognitive brain and into our consciousness. If you rationalize that, the cognitive brain network overtakes and suppresses the emotional fear network.

Symptoms of anxiety disorders are thought to result in part from a disruption in the balance of activity in the emotional centers of the brain rather than in the higher cognitive centers.

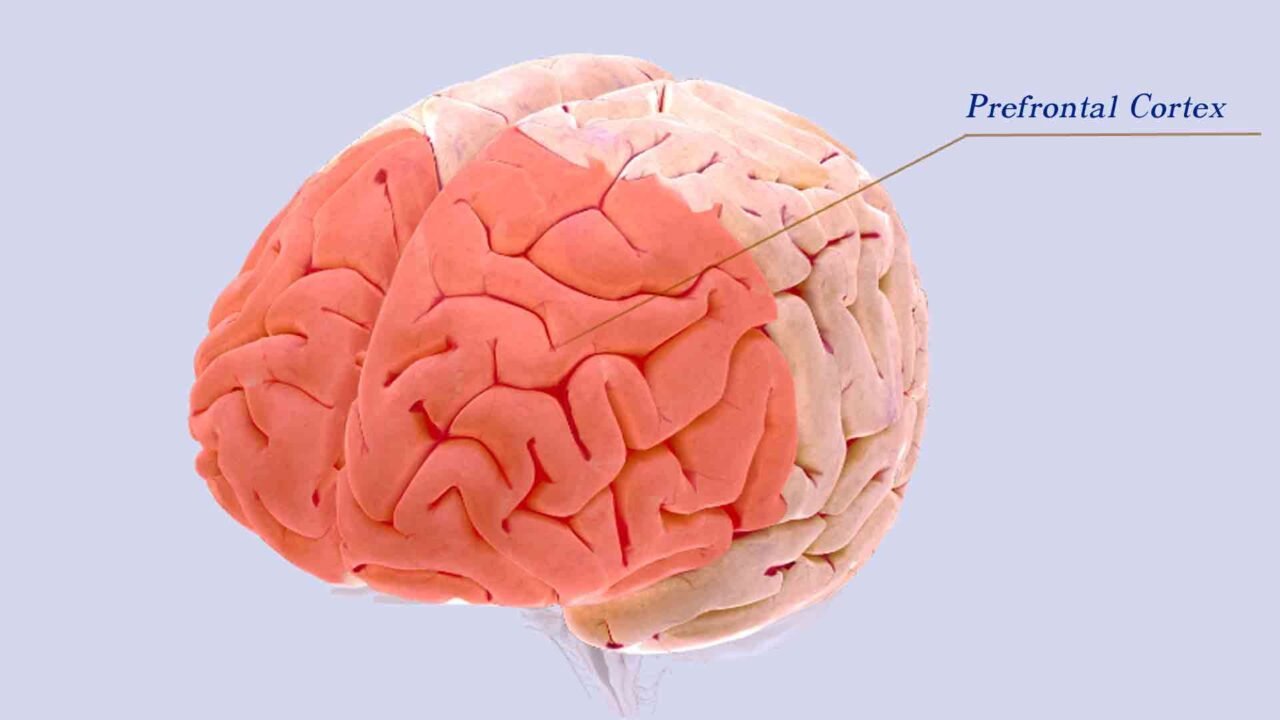

The Role of the Frontal Cortex in Emotion and Anxiety Regulation

The higher cognitive centers of the brain reside in the frontal lobe.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is responsible for executive functions, including planning, decision-making, predicting consequences for potential behaviors, and understanding and moderating social behavior.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) processes information, regulates impulses, and influences mood. This region is crucial for the self-regulation of emotions and the relearning of stimulus-reinforcement associations.

The medial OFC is implicated in the fear of extinction. Functional changes of the medial OFC primarily accompany the successful treatment of spider phobia.

In contrast to mOFC, anterolateral OFC (lOFC) has been associated with adverse effects and obsessions, and thus, dysfunctional lOFC may underlie different aspects of specific anxiety disorders.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is involved in reward processing and visceral emotional responses.

In the healthy brain, these frontal cortical regions regulate impulses, emotions, and behavior via inhibitory top-down control of emotional-processing structures. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is involved in dampening the signals coming from the amygdala. Patients with damage to this brain region are more likely to experience anxiety since the brakes on the amygdala have been lifted.

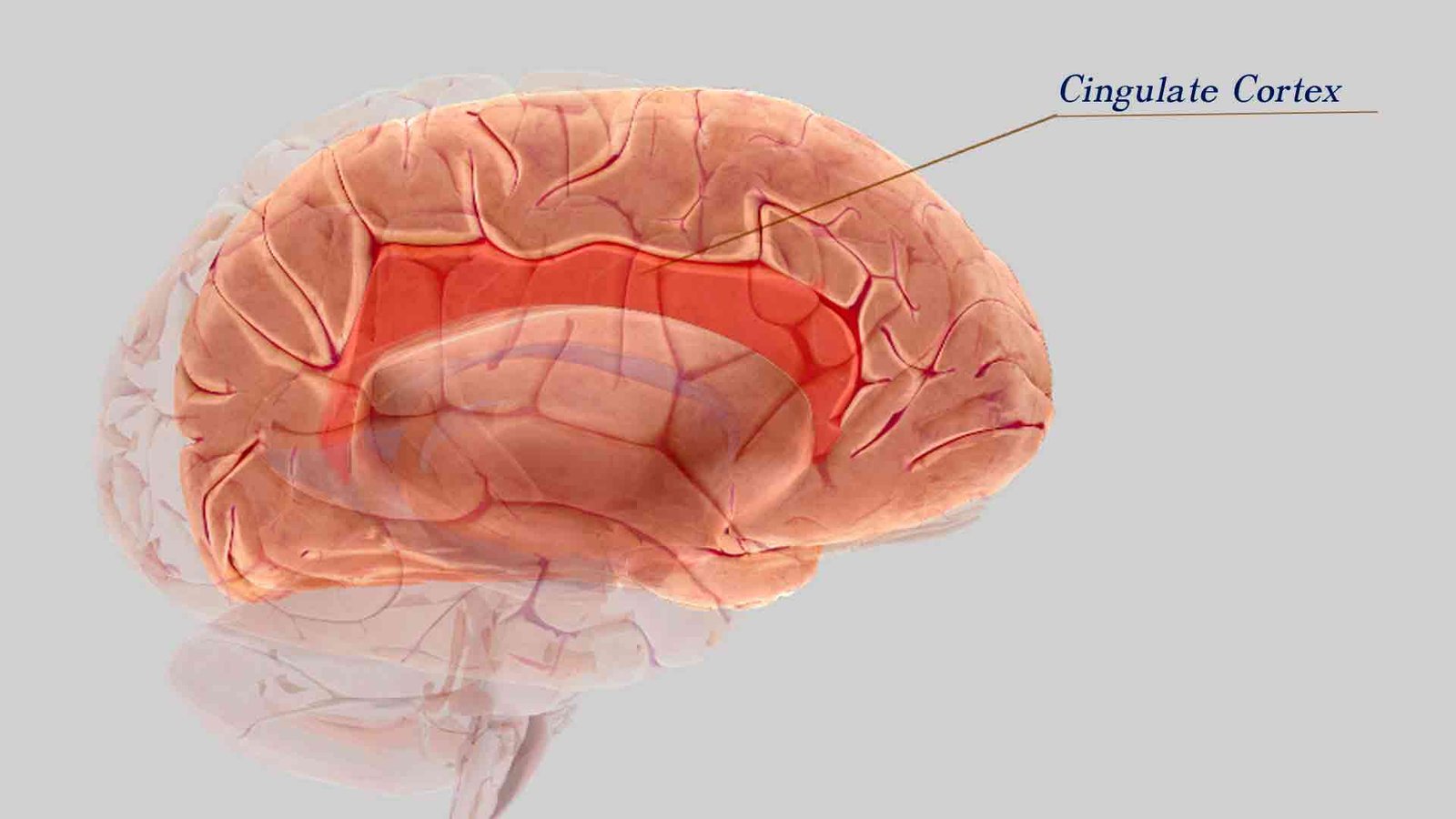

The Limbic Cortex: Its Role in Anxiety and Emotional Processing

The emotional-processing brain structures are referred to as the limbic cortex.

It includes the insular cortex and cingulate cortex. The limbic cortex integrates pain’s sensory, affective, and cognitive components and processes information regarding the internal bodily state. Dysfunction in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) may play an important role in anxiety psychopathology.

A relative gray matter deficit was found in the right anterior cingulate cortex of patients with panic disorder (PD) compared with controls. Deactivation in PCC while listening to threat-related words alternating with emotionally neutral words. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (DACC) amplifies fearful signals from the amygdala. When anxious patients are shown pictures of frightened faces, the DACC and amygdala ramp up their interaction, producing palpable anxiety. People without anxiety show little to no response.

Compared with controls, a relative increase in gray matter volume was also found in the left insula of patients with panic disorder (PD).

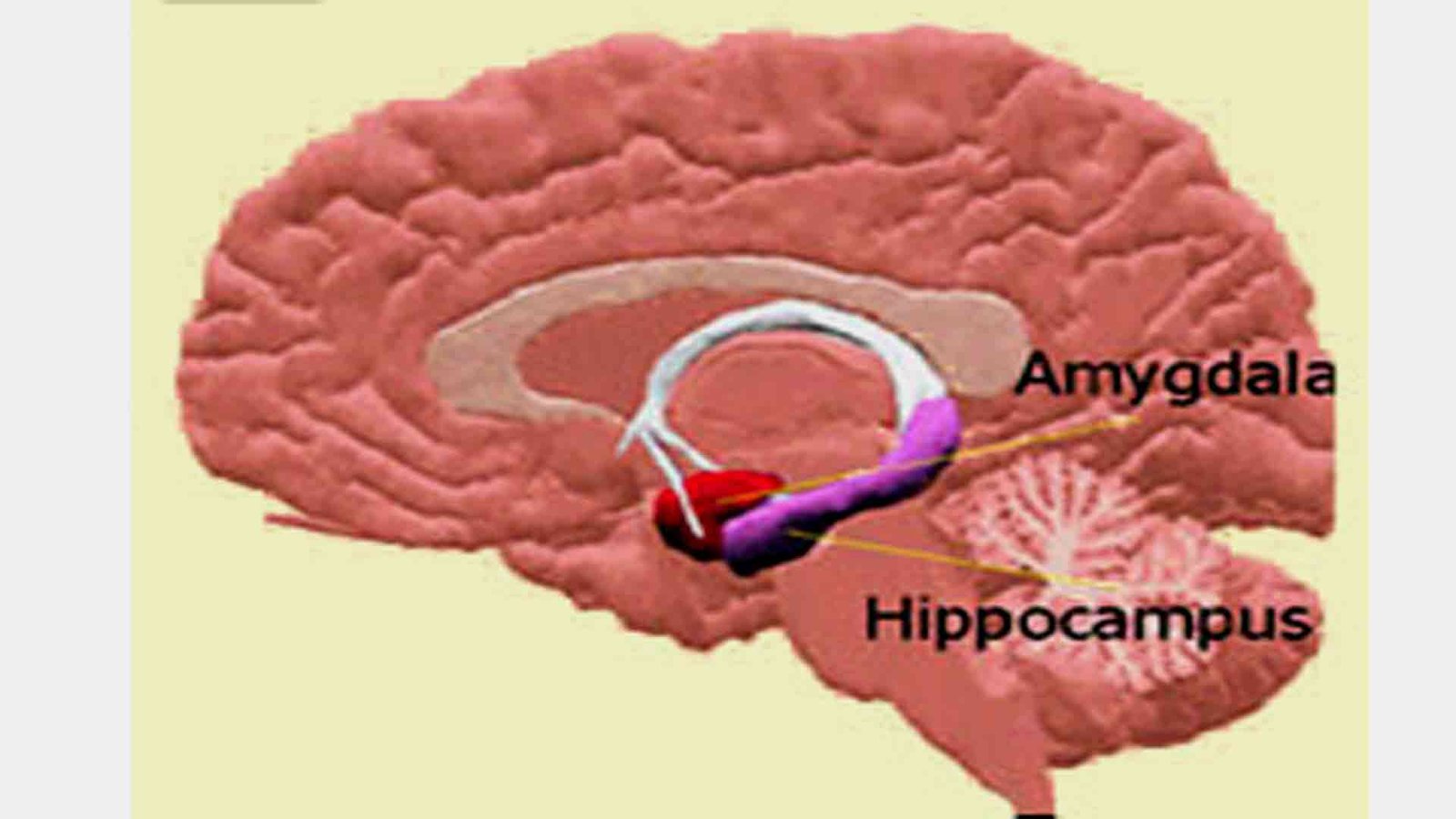

The Hippocampus: Its Role in Stress, Memory, and Anxiety Disorders

The hippocampus is another structure within the limbic system. It has tonic inhibitory control over the hypothalamic stress-response system and plays a role in negative feedback for the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Because all old memories depend on the hippocampus, this structure is involved in anxiety disorders that are generated by memories of painful experiences, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Studies do show that people who have suffered the stress of incest or military combat have a smaller hippocampus. This atrophy of the hippocampus might explain why such people experience explicit memory disturbances, flashbacks, and fragmentary memories of the traumatic events in question. Research shows that the hippocampus is also smaller in some depressed people. Stress, which plays a role in both anxiety and depression, may be a key factor here since there is some evidence that stress may suppress the production of new neurons (nerve cells) in the hippocampus.

Fear and Anxiety: The Amygdala’s Role in Emotional Responses

The amygdala processes emotionally salient external stimuli and initiates the appropriate behavioral response. It is responsible for the expression of fear and aggression, as well as species-specific defensive behaviors, and plays a role in the formation and retrieval of emotional and fear-related memories. The amygdala plays a central role in anxiety disorders. It warns us when danger is present in our environment, triggering the fear reaction and then the fight-or-flight response to get us out of it.

Some studies have shown that monkeys with damage to the amygdala exhibit unusual stoicism in the face of frightening stimuli, such as a nearby snake.

The amygdala generates fear responses, whereas cortical regions, specifically the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC) and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), are implicated in fear extinction. The central nucleus of the amygdala is heavily interconnected with cortical areas, including the limbic cortex. It also receives input from the hippocampus, thalamus, and hypothalamus. It plays a vital role in anxiety disorders that involve specific fears, such as phobias. Researchers have also observed that a group of very anxious children had a larger amygdala, on average, than a group of normal children.

The amygdala acts as a sensor of threats or a lack of control, communicating the need for a reaction to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus, in turn, releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which binds to the adenohypophysis, causing it to produce adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH binds to the adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla.

Brain Structure and Neurotransmitter Imbalances in Anxiety Disorders

Researchers have shown that the left superior temporal gyrus, the midbrain, and the pons are additional structures that exhibit differential increases in gray matter.

In addition to the differences in the size of various brain structures, abnormally high or low activity in a particular region of the brain may be another kind of anomaly that results in anxiety disorders.

In addition to the activity of each brain region, the neurotransmitters providing communication between these regions must also be considered.

Increased activity in emotion-processing brain regions in patients with an anxiety disorder could result from decreased inhibitory signaling by gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) or increased excitatory neurotransmission by glutamate. Well-documented anxiolytic and antidepressant properties of drugs that act primarily on monoaminergic systems have implicated serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the pathogenesis of mood and anxiety disorders.

Neurofeedback for Anxiety Disorders

Understanding Anxiety’s Impact on Health

Chronic anxiety and stress can increase catecholamine release, decrease growth hormones, and aberrantly activate immune and inflammatory cascades. As such, stress and anxiety can directly influence illness progression and can lead to irritable bowel syndrome exacerbations and increased cardiovascular risk. Increased frequency of general anxiety disorder has been found in people with asthma, cancer, and chronic pain.

This comorbidity of anxiety with chronic illness can cause increased morbidity, mortality, and decreased quality of life. Poorly controlled anxiety reduces the quality of life of many healthy individuals and is a crucial symptom of numerous neuropsychiatric and psychosomatic conditions.

Anxiety in Children and Traditional Treatment Approaches

For young children who perceive the world as a threatening place, a wide range of conditions can trigger anxious behaviors that then impair their ability to learn and interact socially with others. Chronic and intense fear early in life affects the development of the stress response system and influences the processing of emotional memories.

Traditional treatments for anxiety include psychological treatments such as cognitive therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, exposure therapy, and self-help groups, as well as pharmacological modalities such as benzodiazepines and antidepressants. While these treatments are common, medications often treat only the symptoms and may cause addiction without addressing the root causes of anxiety.

Although anxiety medication may temporarily help with anxiety relief, it usually doesn’t address the root cause, and it negatively reinforces avoidant behaviors instead of learning how to deal with stress and uncomfortable feelings. Medications treat the symptoms and do not correct the source of the problem in the brain. Besides, many anxiolytics may cause addictions.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety

The most common anxiety treatment is psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, specifically Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Anxiety, has been shown through research to be very effective in addressing the symptoms associated with anxiety.

Neurofeedback vs. Medication for Anxiety Disorders

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy remains a popular treatment for anxiety disorders, but medications often reinforce avoidant behaviors without addressing the root causes of anxiety. Neurofeedback, a non-invasive alternative, offers similar efficacy to medicines without the drawbacks. By teaching the brain to self-regulate, neurofeedback helps reduce or eliminate the need for medications, offering a long-term solution to anxiety. Research suggests that neurofeedback produces stable effects over time, while the benefits of medications usually fade after discontinuation.

Anxiety disorder management with Neurofeedback is almost as effective as medication and helps reduce or eliminate the use of these medications.

How Neurofeedback Works for Anxiety Management

Neurofeedback is all about teaching the brain to self-regulate and reduce or eliminate symptoms of anxiety disorders. Neurofeedback works subconsciously, controlled 90 to 95% of the time. Through measurement and reinforcement, you learn to regulate your brainwave activity. Quite simply, you are reinforced for changing brainwaves at a subconscious level through the use of computers. Almost any brain, regardless of its level of function (or dysfunction), can be trained to function better. Research has shown that the long-term effects of neurofeedback in anxiety disorders are stable over time, in contrast to the anxiolytic medication, which has an impact for a short period after discontinuation.

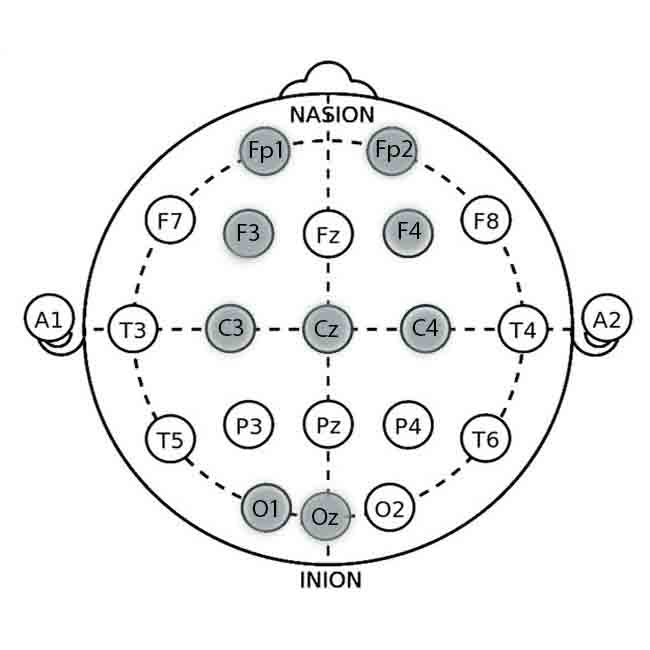

The first step in Neurofeedback for anxiety disorder treatment is to evaluate and measure brainwaves in different brain areas, revealing their functioning and activity. EEG reveals areas of the brain with excessive or deficient activity. It could also show which areas are not communicating well with other regions.

QEEG Brain Mapping

Specific brainwave patterns are associated with certain neuropsychological functions and conditions. Therefore, qEEG brain mapping may yield exact results.

The qEEG analysis allows specialists to see precisely excessive activation in part of the fear network in the brain in anxiety disorders. Once we know the source of the problem, we target that area for change through neurofeedback brain training. This allows you to reshape your brain, not just mask your symptoms.

People suffering from anxiety disorders often have over-activation in brain regions such as the right insula, hippocampus, and amygdala. Theory today suggests that anxiety disorders involve deficits in cognitive skills, such as the control of attention, and these mental aspects of the disorders are the most likely targets for neurofeedback for anxiety disorders management, whose effects are thought to be mediated mainly through cognitive skill enhancement.

Targeting Specific Brainwaves in Neurofeedback for Anxiety

From a neurofeedback management perspective, the alpha band (8-12 Hz) asymmetry with prevalence in the left frontal cortex has emerged as the most prominent electroencephalographic (EEG) correlate of both anxiety and depression in right-handed people, followed by excessive band power in beta 1 (12-20 Hz) and beta two waves (20-30 Hz) in the right parietal lobe. There is also research that shows the association of anxiety disorders with high beta in conjunction with a decrease in Low Beta activity in the temporal lobes.

Neurofeedback for anxiety disorders enables people to control changed brain activation, reducing their anxiety levels consciously.

Neurofeedback Protocols and Long-Term Anxiety Management

Since its first study, anxiety disorder neurofeedback management has used a wide range of EEG target frequency bands and protocols. This includes frequencies in the alpha, beta, and theta ranges, which comprise almost half of the typically measured spectrum of frequencies.

SMR Protocol

Healthy alpha asymmetry and regulation of alpha power bands with Neurofeedback have been successfully used to treat anxiety disorders and depression. Increasing the power of sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) bands (12-15 Hz) over the sensorimotor cortex has been used successfully to improve memory and sleep quality.

Alpha/Beta3 ratio protocol

Increasing the alpha/beta ratio (9.5-12 Hz/23-38 Hz) at the parietal lobe has been shown to improve anxiety, depression, sleep quality, and executive functions.

The combination of both protocols, the SMR followed by the alpha/beta3 ratio, leads to an overall improvement in the symptoms reported by patients with anxiety disorders. The neurofeedback training protocol usually lasts 20 sessions, during which the individual is trained to increase beta 1 (12-15 Hz) at C4 with eyes open, followed by closed-eyes training designed to improve the alpha/beta three ratio (9.5-12 Hz/23-38 Hz) at P4. Researches show marked improvement in anxiety, depression, and sleep quality, as well as some improvement in executive functions.

EEG biofeedback protocols for the treatment of anxiety disorders have included alpha enhancement (e.g., Hardt & Kamiya, 1978), theta enhancement (e.g., Satterfield et al., 1976), and alpha-theta enhancement (Peniston & Kulkosky, 1991) paradigms. Information regarding the location of sensors, frequency bands to be reinforced/inhibited, and the type of feedback is provided below.

Electrode Locations and Effect

Fp1 (Left Prefrontal Cortex):

Location: Frontal pole, 10% of the distance from the Nasion (bridge of the nose).

Relevance: Involved in cognitive control and emotional regulation. Increasing alpha activity here can promote relaxation.

Fp2 (Right Prefrontal Cortex):

Location: Frontal pole, 10% of the distance from the Nasion.

Relevance: Associated with stress and anxiety responses. Training can help balance activity levels and reduce symptoms of anxiety.

F3 (Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex – DLPFC):

Location: The frontal lobe is 30% of the distance from the Nasion to the inion and 20% from the midline.

Relevance: Involved in cognitive control and emotional regulation. Enhancing alpha or SMR activity in this area can help reduce anxiety.

F4 (Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex – DLPFC):

Location: Frontal lobe, analogous to F3 on the right side.

Relevance: Balancing activity with F3 can help regulate anxiety-related imbalances.

Cz (Central Midline):

Location: The scalp vertex, halfway between the Nasion and inion, and equally spaced between the left and right preauricular points (just above the ears).

Relevance: Often used as a reference or ground electrode in neurofeedback sessions, it is also involved in general arousal and relaxation.

Alpha enhancement protocol

- Sensor location – O1, Oz (most common); C3, C4 (less common).

- Reinforced frequencies – 8-13 Hz.

- Reinforced EEG pattern – Percentage of time the patient produces alpha amplitudes above a threshold

(e.g., ten microvolts), or patient production of alpha amplitudes above a set point

(e.g., 19-21 microvolts). - Feedback modality – Auditory (tones and verbal feedback); eyes are typically closed during training.

- Timing of sessions – Ranges from daily to weekly.

Theta enhancement protocol

- Sensor location – Oz or C4.

- Reinforced frequencies – Maintaining 3.5- to 7.5-Hz activity above a preset microvolt threshold while suppressing 8- to 12-Hz production below a specified microvolt threshold

- Feedback modality: It is primarily auditory with the eyes closed; visual feedback is provided when surface electromyographic (EMG) feedback is provided.

- Timing of sessions – Daily to weekly.

How Neurofeedback Training Reduces Anxiety and Enhances Brain Function

During the Neurofeedback procedure, the computer measures brainwave activity through the electrodes placed on the scalp (watch video). When input falls into acceptable and healthy parameters, the system generates pleasant stimuli (audio or video feedback) to reinforce the change. A movie plays consistently with a ding each time a preset goal is achieved. This process is enjoyable, and since the brain craves this simple reinforcement, it typically begins to change within a few seconds of the session’s commencement.

This operant conditioning is continued over numerous neurofeedback sessions to reinforce transient changes in brain function using the patient’s input as a guide. The brain begins to regulate through this reinforcement process, and symptoms start to reduce. With neurofeedback, it is possible to address and treat subconscious fears or worries. This is often the only way to gain access to the origin of anxiety/panic attacks.

Most people require two Neurofeedback sessions per week, and the number of sessions varies based on the individual and the specific issue. While some people notice a reduction in symptoms after the first session, others may experience a gradual improvement over time. The effects are often felt within the first few sessions; further training makes these permanent. Neurofeedback management of anxiety disorders calms the CNS so that a child, teen, or individual with anxiety can learn to manage stress in healthy ways.

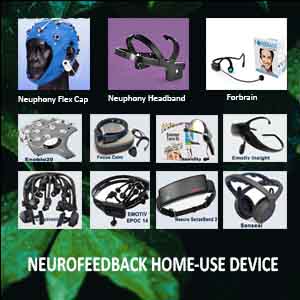

After obtaining stable results with the help of neurofeedback specialists, people with anxiety can continue to perform neurofeedback management of anxiety disorders according to their needs with the help of home-use neurofeedback devices. They are very simple to use and adapted for alpha and beta neurofeedback training, i.e., relaxation and concentration. Additionally, the consistent use of these devices can enhance both short-term and long-term memory, improve sleep quality, and increase stress resistance.

There are also biofeedback home-use devices that can help manage anxiety.

FAQ: Neurofeedback for Anxiety

While Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) addresses the thought patterns behind anxiety and medication manages the symptoms, neurofeedback addresses the root cause by directly retraining dysregulated brain activity.

Neurofeedback often targets areas involved in the “fear network,” such as:

- The Amygdala: The brain’s alarm system for fear and threat.

- The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): Responsible for regulating emotions and impulses.

- The Insula and Anterior Cingulate Cortex: Regions involved in processing internal bodily states and emotional awareness.

- Alpha Asymmetry Training: Aims to increase calming alpha waves in the left frontal cortex.

- SMR Protocol: Increases sensorimotor rhythm (12-15 Hz) to improve relaxation and sleep quality.

- Alpha/Beta3 Ratio Protocol: Increases the ratio of alpha to high-beta waves to reduce anxiety and improve executive function.

A specialist will determine the best protocol based on an individual’s quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) brain map.

Some people feel a reduction in symptoms after the first session, while others experience a gradual improvement over time. Noticeable effects are often felt within the first few sessions. A typical training protocol involves around 20 sessions to create lasting, stable changes in brain function.

Yes, after working with a specialist to establish a foundation, you can use home-use neurofeedback devices for maintenance. These devices are designed to be simple to use and are adapted for training relaxation (alpha waves) and focus (beta waves), helping to consolidate the benefits achieved in clinical sessions.

References:

- E.I. Martin, K.J. Ressler, et al. The Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders: Brain Imaging, Genetics, and Psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009 September; 32(3): 549–575. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2009.05.004.

- Mennella et al. (2017). Frontal alpha asymmetry neurofeedback for the reduction of negative affect and anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy, 92, 32-40.

- Dias, Á. M. et al. (2011). A new neurofeedback protocol for depression. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(01), 374-384.

- Blaskovits F., et al. Effectiveness of neurofeedback therapy for anxiety and stress in adults living with a chronic illness: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports: July 2017, Volume 15, Issue 7, p 1765–1769. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003118

- Scheinost, D., et al. (2013). Orbitofrontal cortex neurofeedback produces lasting changes in contamination anxiety and resting-state connectivity. Translational Psychiatry, 3(4), e250. doi:10.1038/tp.2013.24

- Simkin, D. R., et al. (2014). Quantitative EEG and neurofeedback in children and adolescents: anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, comorbid addiction, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and brain injury. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America, 23(3), 427-464.

- Gomes J.S., et al. A neurofeedback protocol to improve mild anxiety and sleep quality. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, vol.38 no.3 São Paulo July/Sept. 2016, 38:264-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1811

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4145052/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2852103/

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(14)70305-0/fulltext

I’ve been looking for this kind of article is great and let me help someone.

Thank you for sharing this article. I could say that I was able to gain information in this article. Very informative and reliable, great work.

Thank you for sharing this very reliable and informative article. I appreciate this a lot, actually, I love it. It is worth reading and sharing.

Very interesting subject, thanks for posting.