Depression is one of the most common mental disorders and the number one cause of disability worldwide. Traditionally, depression has been treated with therapy and medication, both of which have limitations. Even with medication, countless depression sufferers continue to struggle. Medication doesn’t teach the brain how to get out of the unhealthy brain pattern of depression. While drugs can serve some positive benefits, there are numerous problems with these medications, including unwanted side effects and reliance on the medication. Neurofeedback for depression can help restore healthier brain patterns and eliminate depression by teaching the brain to get “unstuck” and better modulate itself. It works on the root of the problem, altering the brain patterns associated with depression. It can bring lasting brain changes, is non-invasive, and produces no undesirable side effects.

Table of Contents

Toggle- Understanding Depression: A Common Yet Serious Mental Health Condition

- CAUSES OF DEPRESSION

- SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION

- TYPES OF DEPRESSION

- Depression in children and teens

- Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

- The Brain Changes that Matter in Neurofeedback for Depression

- EEG Biomarkers in Neurofeedback for Depression

- TREATMENT FOR DEPRESSION

- NEUROFEEDBACK FOR DEPRESSION. HOW CAN NEUROFEEDBACK HELP?

- NEUROFEEDBACK FOR DEPRESSION. TRAINING PROTOCOLS

- EFFECTIVENESS OF NEUROFEEDBACK FOR DEPRESSION

- OTHER RECOMMENDATION HOW TO COPE WITH DEPRESSION

- FAQ: Neurofeedback for depression

- REFERENCES

Understanding Depression: A Common Yet Serious Mental Health Condition

Feeling down from time to time is a regular part of life. However, when emotions such as hopelessness and despair take hold and won’t go away, you may have depression. More than just sadness in response to life’s struggles and setbacks, depression changes how you think, feel, and function in daily activities. It can interfere with your ability to work, study, eat, sleep, and enjoy life. Just trying to get through the day can be overwhelming. If depression is left untreated, it can become a severe health condition.

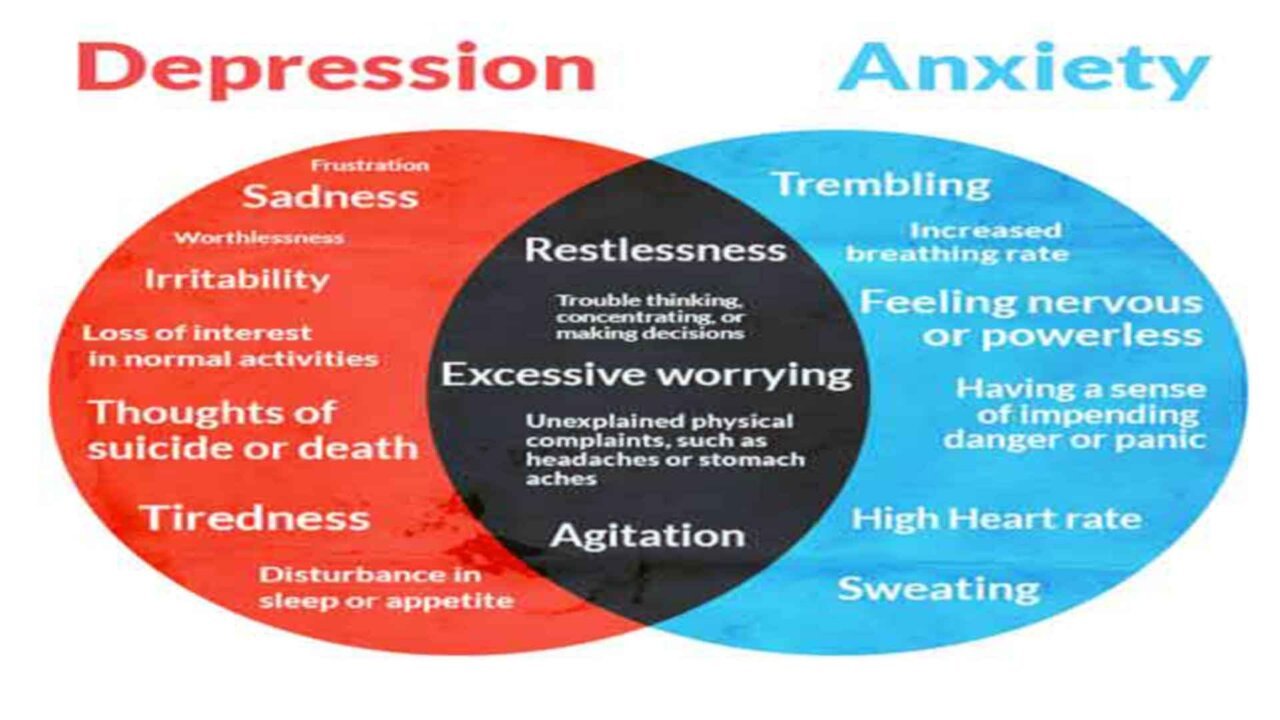

Depression is one of the most common mental disorders and the number one cause of disability worldwide. It can affect anyone at almost any age. It is estimated that 10% to 15% of the general population will experience clinical depression in their lifetime. The World Health Organization estimates 5% of men and 9% of women experience depressive disorders in any given year. Over half of the people who experience depression will experience anxiety at the same time. The financial costs of depression are tremendous, with the global costs per year of depression and anxiety estimated to be $1.15 trillion.

CAUSES OF DEPRESSION

There’s no single cause of depression. It can occur for various reasons and has many triggers.

For some people, an upsetting or stressful life event, such as bereavement, divorce, illness, redundancy, or job or money worries, can be the cause.

Different causes can often combine to trigger depression. For example, you may feel low after being ill and then experience a traumatic event, such as a bereavement, which brings on depression.

People often talk about a “downward spiral” of events that leads to depression. For example, if your relationships with your partner break down, you’re likely to feel low, you may stop seeing friends and family, and you may start drinking more. All of this can make you feel worse and trigger depression.

Some studies have also suggested that you’re more likely to get depression as you get older and that it’s more common in people who live in complex social and economic circumstances.

Common causes of depression

Stressful events

Most people take time to come to terms with stressful events, such as bereavement or a relationship breakdown. When these stressful events occur, your risk of becoming depressed increases if you stop seeing your friends and family and try to deal with your problems on your own.

Personality

You may be more vulnerable to depression if you have certain personality traits, such as low self-esteem or being overly self-critical. This may be due to the genes you’ve inherited from your parents, your early-life experiences, or both.

Family history

Since it can run in families, some people likely have a genetic susceptibility to depression. If someone in your family has had depression in the past, such as a parent, sister, or brother, it’s more likely that you’ll also develop it. However, there is no single “depression” gene. Your lifestyle choices, relationships, and coping skills matter as much as genetics.

Giving birth

Some women are particularly vulnerable to depression after pregnancy. The hormonal and physical changes, as well as the added responsibility of a new life, can lead to postnatal depression.

Loneliness and isolation

Feelings of loneliness, caused by things such as becoming cut off from your family and friends, can increase your risk of depression. However, having depression can cause you to withdraw from others, exacerbating feelings of isolation.

Alcohol and drugs

When life is getting people down, some of them try to cope by drinking too much alcohol or taking drugs. This can result in a spiral of depression.

Cannabis can help you relax, but there’s evidence that it can also bring on depression, particularly in teenagers.

“Drowning your sorrows” with a drink is also not recommended. Alcohol affects the chemistry of the brain, which increases the risk of depression.

Chronic illness or pain

The mind links to the body. If you are experiencing a physical health problem, you may discover changes in your mental health as well.

You may have a higher risk of depression if you have a longstanding or life-threatening illness, such as coronary heart disease or cancer.

Head injuries are also an often under-recognized cause of depression. A severe head injury can trigger mood swings and emotional problems.

Some people may have an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) resulting from problems with their immune system. In rarer cases, a minor head injury can damage the pituitary gland, a pea-sized gland at the base of the brain that produces thyroid-stimulating hormones.

This can cause many symptoms, such as extreme tiredness and a lack of interest in sex (loss of libido), which can, in turn, lead to depression.

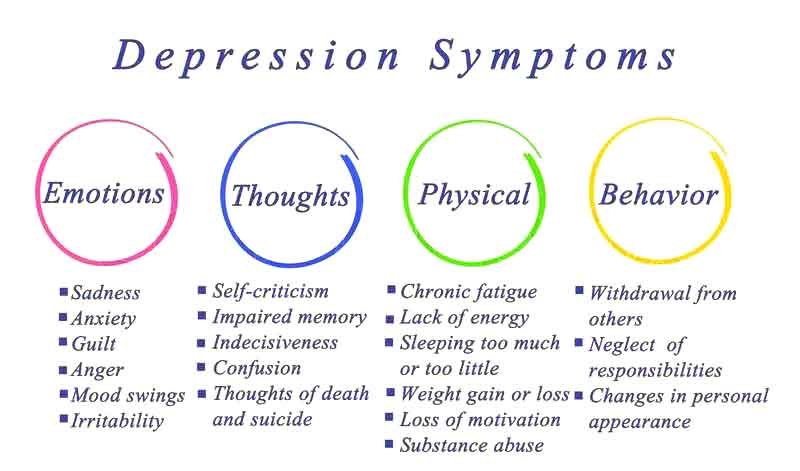

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION

Depression varies from person to person, but there are some common signs and symptoms. It’s important to remember that these symptoms can be part of life’s average lows. But the more symptoms you have, the stronger they are, and the longer they’ve lasted, the more likely it is that you’re dealing with depression.

Depression is an ongoing problem, not a passing one. It consists of episodes during which the symptoms last at least two weeks. Depression can last for several weeks, months, or years.

10 common symptoms of depression:

- Feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, emptiness, despair, and sadness. A bleak outlook – nothing will ever improve, and you can do nothing to improve your situation.

- Loss of interest in previously pleasurable daily activities. You no longer care about former hobbies, pastimes, social activities, or sex. You’ve lost your ability to feel joy and pleasure.

- Appetite or weight changes. Significant weight loss or weight gain – a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month.

- Sleep changes. Either insomnia, especially waking in the early morning hours, or oversleeping.

- Anger or irritability. Feeling agitated, restless, or even violent. Your tolerance level is low, your temper is short, and everything and everyone gets on your nerves.

- Loss of energy. You may feel fatigued, sluggish, and physically drained. Your whole body may feel heavy, and even small tasks may be exhausting or take longer.

- Self-loathing. Strong feelings of worthlessness or guilt. You harshly criticize yourself for perceived faults and mistakes.

- Reckless behavior. You engage in escapist behavior such as substance abuse, compulsive gambling, reckless driving, or dangerous sports.

- Concentration problems. Trouble focusing, making decisions, or remembering things.

- Unexplained aches and pains. There has been an increase in physical complaints such as headaches, back pain, aching muscles, stomach pain, breast tenderness, and bloating.

TYPES OF DEPRESSION

Depression comes in many shapes and forms. Defining the severity of depression—whether it’s mild, moderate, or significant—can be complicated. However, understanding the type of depression you have can help you manage your symptoms and receive the most effective treatment.

Mild and moderate depression

Mild and moderate depression are the most common types of depression. More than simply feeling blue, the symptoms of mild depression can interfere with your daily life, robbing you of joy and motivation. Those symptoms become amplified in moderate depression and can lead to a decline in confidence and self-esteem.

Recurrent, mild depression (dysthymia)

Dysthymia is a type of chronic “low-grade” depression. More days than not, you feel mildly or moderately depressed, although you may have brief periods of everyday mood.

- The symptoms of dysthymia are not as intense as the symptoms of major depression, but they last a long time (at least two years).

- Some people also experience major depressive episodes on top of dysthymia, a condition known as “double depression.”

- If you suffer from dysthymia, you may feel like you’ve always been depressed. Or you may think that your continuous low mood is “just the way you are.”

Major depression

Major depression occurs less frequently than mild or moderate depression and features severe, relentless symptoms.

- Left untreated, major depression typically lasts for about six months.

- Some people experience just a single depressive episode in their lifetime, but major depression can be a recurring disorder.

Atypical depression

Atypical depression is a common subtype of major depression with a specific symptom pattern. It responds better to some therapies and medications than others, so identifying it can be helpful.

- People with atypical depression experience a temporary mood lift in response to positive events, such as after receiving good news or while out with friends.

- Other symptoms of atypical depression include weight gain, increased appetite, sleeping excessively, a heavy feeling in the arms and legs, and sensitivity to rejection.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

For some people, the reduced daylight hours of winter lead to a form of depression known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). SAD affects about 1% to 2% of the population, particularly women and young people. Seasonal Affective Disorder can make you feel completely different from who you are in the summer: hopeless, sad, tense, or stressed, with no interest in friends or activities you normally love. SAD usually begins in the fall or winter, when the days grow shorter, and lasts until spring’s brighter days.

Understanding the underlying cause of your depression may help you overcome the problem. However, whether you’re able to isolate the causes of your depression or not, the most important thing is to recognize that you have a problem, reach out for support, and pursue the coping strategies that can help you to feel better.

Depression in children and teens

Biological and Genetic Factors in Childhood Depression

Approximately 2% of preschool and school-age children are also affected by depression. A depressive disorder in children does not have one specific cause. Biologically, depression is linked to a deficiency of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain, smaller sizes in some brain areas, and increased activity in other parts of the brain. Girls are more likely than boys to receive a diagnosis of depression, which researchers believe results from various factors, including biological differences based on gender and how society encourages girls to interpret and respond to their experiences differently from boys.

There is thought to be at least a partial genetic component to the pattern of children and teens with a depressed parent, who are as much as four times more likely to develop the disorder. Children who have depression or anxiety are more prone to have other biological problems, like low birth weight, suffering from a physical condition, trouble sleeping, etc.

Psychological and Environmental Contributors to Childhood Depression

Psychological contributors to depression include low self-esteem, negative social skills, negative body image, being excessively self-critical, and often feeling helpless when dealing with adverse events. Children who suffer from conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), clinical anxiety, or who have cognitive or learning problems, as well as trouble engaging in social activities, also have a higher risk of developing depression.

Depression may be a reaction to life stresses, like trauma, including verbal, physical, or sexual abuse, the death of a loved one, school problems, bullying, or suffering from peer pressure.

Other contributors to this condition include poverty and financial difficulties in general, exposure to violence, social isolation, parental conflict, divorce, and other causes of disruptions to family life. Children who have limited physical activity, poor school performance, or who lose a relationship are at higher risk for developing depression, as well.

General symptoms of depression in children

Impact of Depression on Daily Functioning and Major Symptoms

Depression often prevents sufferers from performing daily activities, such as getting out of bed, getting dressed, excelling at school, or playing with peers. General symptoms of a major depressive episode, regardless of age, include having a depressed mood or irritability or difficulty experiencing pleasure for at least two weeks and having at least five of the following signs and symptoms:

- Feeling sad or blue and irritable or seeming that way as observed by others (for example, tearfulness or otherwise looking persistently sad or angry),

- Significant appetite changes, with or without substantial weight loss, failing to gain weight appropriately, or gaining excessive weight,

- Change in sleep pattern: trouble sleeping or sleeping too much,

- Physical agitation or retardation (for example, restlessness or feeling slowed down),

- Fatigue or low energy/loss of energy,

- Difficulty concentrating,

- Feeling worthless, excessively guilty, or tending to self-blame,

- Thoughts of death or suicide

Childhood and Teen Depression: Symptoms and Behavioral Changes

Children with depression may also experience the classic symptoms, but may exhibit other symptoms as well, including:

- Impaired performance of schoolwork,

- Persistent boredom,

- Quickness to anger,

- Frequent physical complaints, like headaches and stomachaches,

- More risk-taking behaviors and less concern for their safety (examples of risk-taking behaviors in children include unsafe play, like climbing excessively high or running in the street).

Depression in infants

Parents of infants and children with depression often report noticing the following behavior changes in the child:

- Crying more often or more quickly,

- Increased sensitivity to criticism or other negative experiences,

- More irritable mood than usual or compared to others their age and gender, leading to vocal or physical outbursts, defiant, destructive, angry, or other acting out behaviors,

- Eating patterns, sleeping patterns, or a significant increase or decrease in weight change, or the child fails to achieve the appropriate weight gain for their age,

- Unexplained physical complaints (for example, headaches or abdominal pain),

- Social withdrawal, in that the youth spends more time alone, away from friends and family,

- Developing more “clinginess” and more dependent on specific relationships,

- Overly pessimistic, hopeless, helpless, excessively guilty, or feeling worthless,

- Expressing thoughts about hurting him or herself or engaging in self-injury behavior,

- Young children may act younger than their age or than they had before (regress).

- Younger children may have difficulty expressing how they feel in words. This can make it harder for them to explain their feelings of sadness.

Physical changes, peer pressure, and other factors can contribute to depression in teenagers. They may experience some of the following symptoms:

- Withdrawing from friends and family,

- Difficulty concentrating on schoolwork,

- Feeling guilty, helpless, or worthless,

- Restlessness, such as an inability to sit still

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

For over 40 years, clinicians regarded the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (often abbreviated as HRSD, HDRS, or Ham-D) as the ‘gold standard’ and the most widely used assessment scale for depression.

The widely available scale has two standard versions: 17 or 21 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 4.

The first 17 items measure the severity of depressive symptoms. For example, the interviewer rates the level of agitation clinically noted during the interview or how the mood impacts an individual’s work or leisure pursuits.

The extra four items on the extended 21-point scale measure factors that might be related to depression but are not thought to be measures of severity, such as paranoia or obsessive and compulsive symptoms.

Classification of symptoms can be expanded to:

- 0 – absent;

- 1 – mild;

- 2 – moderate;

- 3 – severe;

- 4 – incapacitating

In general, the higher the total scores, the more severe the depression.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale is designed for clinicians to administer after a structured or unstructured interview to determine the patient’s symptoms. The total score is calculated by summing the individual scores from each question.

- Scores below seven generally represent the absence or remission of depression,

- Scores between 7-17 represent mild depression,

- Scores between 18-24 represent moderate depression,

- Scores 25 and above represent severe depression

The maximum score is 52 on the 17-point scale.

The Brain Changes that Matter in Neurofeedback for Depression

Brain Chemistry Imbalances

The Role of Neurotransmitters in Depression

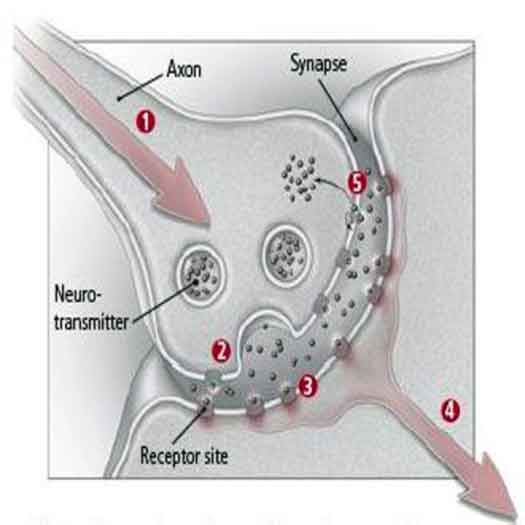

One potential biological cause of depression is an imbalance in the neurotransmitters that are involved in mood regulation. Certain neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, play crucial roles in regulating mood.

Neurotransmitters are chemical substances that facilitate communication between different areas of the brain. When certain neurotransmitters are in short supply, it may lead to the symptoms we recognize as clinical depression.

It’s often said that depression results from a chemical imbalance, but research suggests that depression doesn’t spring from simply having too much or too little of certain brain chemicals. Two people might have similar symptoms of depression, but the problem on the inside, and therefore what treatments will work best, may be entirely different.

How Neurotransmitters Work in the Brain

Neurotransmitters are chemicals that relay messages from neuron to neuron. Antidepressant medications tend to increase the concentration of these substances in the spaces between neurons (the synapses). In many cases, this shift appears to give the system enough of a nudge so that the brain can do its job more effectively.

A combination of electrical and chemical signals allows communication within and between neurons. When a neuron becomes activated, it passes an electrical signal from the cell body down the axon to its end (known as the axon terminal), where chemical messengers called neurotransmitters are stored. The signal releases neurotransmitters into the space between the neuron and the dendrite of a neighboring neuron, called a synapse.

The Neurotransmitter Cycle and Reuptake Process

As the concentration of a neurotransmitter rises in the synapse, neurotransmitter molecules begin to bind with receptors embedded in the membranes of the two neurons. Once the first neuron has released a certain amount of the neurotransmitter, a feedback mechanism (controlled by that neuron’s receptors) instructs the neuron to stop pumping it out and start taking it back into the cell. This process is called reabsorption or reuptake. Enzymes break down the remaining neurotransmitter molecules into smaller particles.

1. An electrical signal travels down the axon.

2. Chemical neurotransmitter molecules are released.

3. The neurotransmitter molecules bind to receptor sites.

4. The second neuron picks up the signal and is either passed along or halted.

5. The first neuron also picks up the signal, causing reuptake, the process by which the cell that released the neurotransmitter takes back some of the remaining molecules.

Brain cells usually produce neurotransmitters that keep senses, learning, movement, and mood perking along. But in some people who are severely depressed or manic, the complex systems that accomplish this go awry.

Key Neurotransmitters Involved in Depression

Scientists have identified many different neurotransmitters. Here is a description of a few believed to play a role in depression:

- Acetylcholine enhances memory and is involved in learning and recall.

- Serotonin helps regulate sleep, appetite, and mood and inhibits pain. Research supports the idea that some depressed people have reduced serotonin transmission. Low levels of serotonin byproducts have been linked to a higher risk for suicide.

- Norepinephrine constricts blood vessels, raising blood pressure. It may trigger anxiety and be involved in some types of depression. It also seems to help determine motivation and reward.

- Dopamine is essential to movement. It also influences motivation and influences how a person perceives reality. Problems in dopamine transmission have been associated with psychosis, a severe form of distorted thinking characterized by hallucinations or delusions. It’s also involved in the brain’s reward system, so it is thought to play a role in substance abuse.

- Glutamate is a small molecule believed to act as an excitatory neurotransmitter and to play a role in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Lithium carbonate, a well-known mood stabilizer used to treat bipolar disorder, helps prevent damage to neurons in the brains of rats exposed to high levels of glutamate. Other animal research suggests that lithium might stabilize glutamate reuptake. This mechanism may explain how the drug smoothes out the highs of mania and the lows of depression in the long term.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an amino acid that researchers believe acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. It is thought to help quell anxiety.

The Neurotransmitter Theory and Treatments for Depression

The neurotransmitter theory of depression suggests that having too much or too little of certain neurotransmitters causes, or at least contributes to, depression. While this explanation is often cited as a significant cause of depression, it remains unproven, and many experts believe that it doesn’t paint a complete picture of the complex factors that contribute to depression.

Medications to treat depression often focus on altering the levels of certain chemicals in the brain. Some of these treatments include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

Areas of the brain affected by depression

Certain areas of the brain help regulate mood. Researchers believe that nerve cell connections, nerve cell growth, and the functioning of nerve circuits are more important than levels of specific brain chemicals and that these factors have a significant impact on depression.

The use of brain imaging technology (positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)) has led to a better understanding of which brain regions regulate mood and how depression may affect other functions, such as memory.

Many functional neuroimaging studies on mood disorders have shown evidence for dysfunction in the medial frontal cortex (MFA and PFm), the orbital frontal cortex (PFo), and the medial and anterior temporal lobes.

Compared with healthy controls, patients with MDD show altered activation in the orbital and medial frontal cortex during exposure to emotionally charged stimuli and during reward-processing tasks. Patients with cerebrovascular disease who develop depression have lesions in the orbital and medial frontal cortex, but other cerebrovascular patients – those without depression – do not.

Patients with Parkinson’s disease who manifest depression show altered metabolism or blood flow in the orbital and medial frontal cortex compared to non-depressed Parkinson’s patients or healthy controls. Furthermore, cortical volume and thickness reductions occur in several parts of the frontal cortex in depressed patients, with the most reliable and best-characterized abnormalities occurring in the PFo area, the sulcal part, and the subgenual frontal cortex. In these critical parts of the MFa, the reduction in cortical volume arises before the onset of symptoms in patients at high familial risk for depression, appears early in the course of the illness, persists across depressive episodes, and occurs consistently in the most severe cases.

Brain areas that play a significant role in depression include the amygdala, thalamus, and hippocampus.

Amygdala

The amygdala is part of the limbic system, a group of structures deep in the brain associated with emotions such as anger, pleasure, sorrow, fear, and sexual arousal. It is activated when a person recalls emotionally charged memories, such as a frightening situation. Activity in the amygdala is higher when a person is sad or clinically depressed, and this increased activity continues even after recovery from depression.

Thalamus

The thalamus receives most sensory information and relays it to the appropriate part of the cerebral cortex, which directs high-level functions such as speech, behavioral reactions, movement, thinking, and learning. Some research suggests that bipolar disorder may result from problems in the thalamus, which helps link sensory input to pleasant and unpleasant feelings.

Hippocampus

The Role of the Hippocampus in Depression

The hippocampus is part of the limbic system and is central to long-term memory and recollection processing. The interplay between the hippocampus and the amygdala might account for the adage “once bitten, twice shy.” This part of the brain registers fear when a barking, aggressive dog confronts you, and the memory of such an experience may make you wary of dogs you come across later in life.

Research shows that the hippocampus is 9% to 13% smaller in some depressed people compared with those who were not depressed. Stress, which plays a role in depression, may be a key factor here since experts believe that stress can suppress the production of new neurons (nerve cells) in the hippocampus. Researchers are exploring possible links between the sluggish production of new neurons in the hippocampus and low moods.

How Neurofeedback for Depression and EEG Studies Aid Depression Treatment

An exciting aspect of antidepressants supports the neuron production theory. While these medications quickly boost neurotransmitter levels, it often takes weeks for people to feel relief from their depression symptoms. This delay suggests that mood improves as neurons grow and form new connections, a process that takes time. This is where neurofeedback for depression proves to be highly effective.

Neurofeedback for depression stimulates positive brain neuroplasticity, rewires neuron connections, and enhances brain function by creating a healthy neural network. Changes in brain region activity in patients with depression can be detected using electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings. EEG offers new diagnostic and predictive possibilities for depression. In 2008, researchers discovered a simple EEG marker, Alpha asymmetry, which could predict a patient’s response to antidepressants even before treatment begins. This finding opens new avenues for personalizing treatment and provides renewed hope for patients and healthcare practitioners.

EEG Biomarkers in Neurofeedback for Depression

Brain Networks and Depression: Insights from EEG Studies

Specific brain networks mediate distinct emotions and behaviors, and changes in interaction patterns are associated with differential cerebral activation. EEG studies provide valuable information about brain functioning patterns during cognitive or emotional tasks in patients with depression.

With a quantitative electroencephalogram (QEEG), it is possible to observe several patterns that include optimal states of psychic balance but also states of fear, anxiety, panic, anger, impatience, and depression.

Studies have identified specific symptoms in the depressed population for two types of depression: one with symptoms of hopelessness and another with symptoms of agitation.

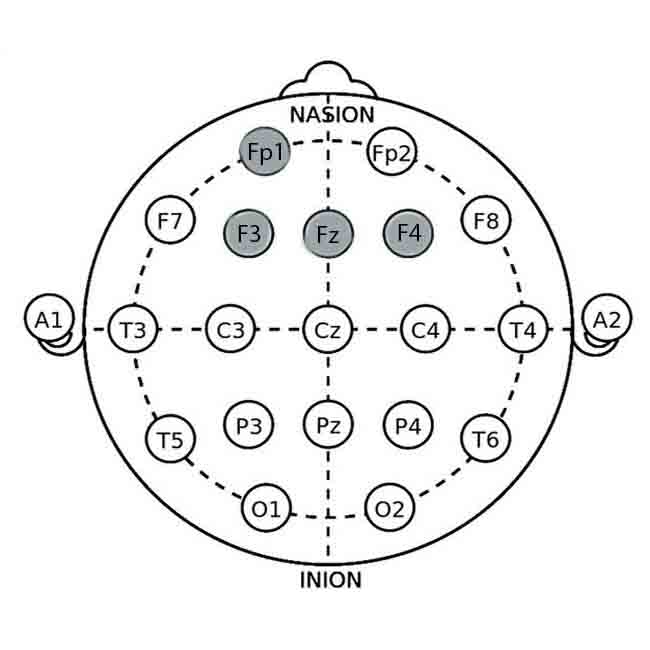

Types of Depression: Hopelessness and Agitated Depression

The symptoms of depression with hopelessness are sadness, loss or significant decline of interest in performing activities previously considered pleasurable, social withdrawal, altered appetite, changes in sleep quality, slowing of speech, and, in some cases, mutism, fatigue, guilty feelings, cognitive disorders, and thoughts related to death. These symptoms are associated with a reversal or asymmetry of alpha waves (8- 12 Hz). Thus, in the average non-depressed population, the importance of the right hemisphere was observed, represented by eight even points (Fp2, F4, F8, C4, T4, P4, T6, and O2) of the international 10-20 electroencephalography mapping system.

These points, in the average non-depressed population, contained around 10 to 15% more alpha waves when compared to the left hemisphere represented by eight odd points (Fp1, F3, F7, C3, T3, P3, T5, and O1), as the alpha waves emit less energy compared to beta waves. This same ideal alpha pattern is expected in the posterior region of the brain at five points (T5, P3, Pz, P4, and T6) when compared to the anterior region, also at five points (F7, F3, Fz, F4, and F8), totaling 26 points, divided into two groups of 13.

The symptoms of agitated depression are irritation, impatience, overemotional, and difficulty concentrating and paying attention, and subjects struggle to create a routine and maintain it. These symptoms are linked to reversals of beta waves (15-23 Hz), which are in the non-depressed population expected to be around 5% higher in the left hemisphere (Fp1, F3, F7, C3, T3, P3, T5, and O1) and in the anterior brain (F7, F3, Fz, F4 and F8) compared to the right hemisphere (Fp2, F4, F8, C4, T4, P4, T6 and O2) and posterior portion of the brain (T5, P3, Pz, P4 and T6), respectively.

QEEG and Neurofeedback for Depression Treatment

In 2008, it was found that a very simple electroencephalographic marker (Alpha asymmetry) could be used not only for diagnostic but also for prognostic purposes: to predict the response to antidepressants before the initiation of pharmacologic treatment, which could aid in the choice of treatment.

While qEEG shows excellent promise in predicting antidepressant medication response and ending the need for lengthy “medication trials,” neurofeedback for depression has been repeatedly found effective in activating brain areas responsible for depression and helping people re-engage with life.

The use of qEEG to map brain function makes the depressed brain visible. Using qEEG, we can see the brain areas that have become less active, reflecting the patient’s disengagement. More importantly, we can target these areas with neurofeedback for depression to reactivate them, allowing the brain to normalize itself.

TREATMENT FOR DEPRESSION

Limitations of Traditional Depression Treatments

Traditionally, depression has been treated with therapy and medication, both of which have limitations.

Antidepressants can help treat moderate-to-severe depression. Several classes of antidepressants are available:

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- tricyclic antidepressants

- atypical antidepressants

- selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

Challenges with Medication and Response Rates

Specific side effects of antidepressants can worsen depression in a small percentage of individuals:

- nausea

- headaches

- sleep disturbances

- agitation

- sexual problems

- suicidal thoughts

- irritability

Even with medication, countless depression sufferers continue to struggle. Medication doesn’t teach the brain how to get out of the unhealthy brain pattern of depression. While drugs can serve some positive benefits, there are numerous problems with these medications, including unwanted side effects and reliance on the medication, making it difficult to stop taking them and manage one’s mood on one’s own. If medications are stopped, symptoms often return. In addition, people can become tolerant of medications, necessitating a dosage increase or medication change, which may produce new side effects. Despite the availability of effective clinical treatments for depression, 30-40% of these patients still fail to respond significantly to antidepressant therapy.

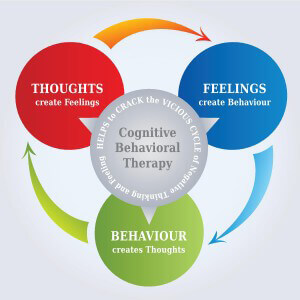

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Neurofeedback for Depression

Depression is a multifaceted mental health condition that affects millions worldwide, impacting their emotional well-being, relationships, and daily functioning. While there are various therapeutic approaches to addressing depression, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) stands out as one of the most influential and evidence-based treatments available.

By understanding the underlying mechanisms of CBT and its application in treating depressive symptoms, mental health professionals can equip themselves with powerful tools to assist individuals in overcoming this debilitating condition.

Through a collaborative and empowering approach, CBT offers hope and healing to those navigating the complex terrain of depression, guiding them toward a brighter and more fulfilling future.

Neurofeedback for depression can help restore healthier brain patterns and eliminate depression by teaching the brain to get “unstuck” and better modulate itself. It teaches the brain to regulate mood. Neurofeedback for depression works on the root of the problem, altering the brain patterns associated with depression. It can bring lasting brain changes, is non-invasive, and produces no undesirable side effects.

NEUROFEEDBACK FOR DEPRESSION. HOW CAN NEUROFEEDBACK HELP?

People who have depression show asymmetry in their frontal lobes. Specifically, the left frontal lobe has significantly less activation in people with depression than in people without depression. Decreased left-sided frontal activation is thought to be associated with a deficit in the approach system (which can generate positive moods). Hence, people with these deficits are more prone to depressive disorders.

Right-sided frontal activation is related to withdrawal-related emotions, such as anxiety disorders. Interestingly, this right-sided activation was associated with selective spatial deficits, which are often reported to accompany depression and may account for the issues with the decoding of nonverbal behavior in people with depression.

Underlying pathophysiological mechanisms have been identified in depression, and research has shown that neurofeedback for depression can target these physiological mechanisms to reduce depressive symptoms.

In 2016, Wang and colleagues highlighted the benefits of neurofeedback for depression on the left and correct frontal activity alpha asymmetry in patients with major depressive disorder.

In 2017, studies by Young and colleagues found evidence to suggest that neurofeedback for depression can significantly decrease depressive symptoms by increasing activity surrounding positive memories. The study suggests a strong correlation between the roles of the amygdala and the recovery of depression.

Young and colleagues (2018) investigated the correlations between changes in depression scores and changes in amygdala connectivity and the effects of neurofeedback training on these changes. They found that neurofeedback for depression increased connectivity between the amygdala and regions involved in self-referential, salience, and reward processing. Results showed that the specific amygdala connectivity was significantly correlated with improvement in depressive symptoms.

NEUROFEEDBACK FOR DEPRESSION. TRAINING PROTOCOLS

Neurofeedback represents an exciting complementary option in the treatment of depression that builds upon a vast body of research on electroencephalographic correlates of depression.

The most commonly used neurofeedback training protocols for depression focus on Alpha interhemispheric asymmetry and the Theta/Beta ratio in the left prefrontal cortex. In some cases, to reduce anxiety, it may be necessary to reinforce the decrease of Beta-3.

The Hammond depression neurofeedback training protocol – reinforces beta arousal while inhibiting alpha and theta arousal in the left frontal area at electrode sites Fp1 and F3.

Patients should receive active neurofeedback from the left amygdala (LA) or the left horizontal segment of the intraparietal sulcus (control region). Pre-/post- resting-state functional connectivity measures showed that abnormal LA hypo-connectivity in depressed patients was reversed after therapy with neurofeedback for depression.

Clinical experience demonstrated that occasionally a patient reported becoming overactivated by the reinforcement of 15-18 Hz beta, feeling somewhat more irritable and anxious, and having some difficulty falling asleep. Therefore, the protocol was modified so that while inhibiting alpha and theta activity, 15-18 Hz beta was reinforced for 20-22 minutes, and then the reinforcement band was changed to 12-15 Hz for the last 8-10 minutes.

Key Electrode Application Sites to Perform Neurofeedback for Depression Treatment

1. F3 (Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex – DLPFC):

- Location: Frontal lobe, 30% of the distance from the nasion (bridge of the nose) to the inion (the prominent bump at the back of the head) and 20% from the midline.

- Relevance: Associated with positive mood regulation and approach behavior. Activity in this area is often reduced in individuals with depression.

2. F4 (Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex – DLPFC):

- Location: Frontal lobe, analogous to F3 on the right side of the head.

- Relevance: While F4 is often related to negative emotions, balancing activity between F3 and F4 can be crucial in mood regulation.

3. Fp1 (Left Prefrontal Cortex):

- Location: Frontal pole, 10% of the distance from the tip.

- Relevance: Involved in executive function and mood regulation. Targeting Fp1 can help enhance positive affect and cognitive control.

4. Cz (Central Midline):

- Location: The scalp vertex, halfway between the nasion and inion, and equally spaced between the left and right preauricular points (just above the ears).

- Relevance: Often used as a reference or ground electrode in neurofeedback sessions.

Neurofeedback Protocols for Depression Management

Alpha Asymmetry Protocol

This protocol balances the alpha wave activity between the left and right prefrontal cortex, particularly at F3 (left) and F4 (right).

- Target Brainwaves: Alpha waves (8-12 Hz)

- Goal: Increase alpha activity at F3 and decrease alpha activity at F4 to reduce left-right asymmetry, as greater left alpha activity relative to the right is often associated with depression.

Procedure:

1. Electrode Placement: Place electrodes at F3, F4, and Cz (reference).

2. Baseline Recording: Record baseline alpha activity for 5-10 minutes.

3. Feedback Mechanism: Provide real-time feedback using visual (e.g., a moving bar or video) or auditory (e.g., tone) cues. When the desired alpha asymmetry is achieved (i.e., more balanced alpha activity), the feedback becomes positive (e.g., the bar grows, the video plays, or the tone changes pleasantly).

4. Training Sessions: Conduct 20-30 minutes of training sessions, 2-3 times per week, for 20-40 sessions.

5. Progress Monitoring: Use depression rating scales and follow-up qEEG to assess changes.

Alpha-Theta Training

This protocol focuses on increasing alpha and theta waves to promote relaxation and reduce anxiety, which can help alleviate depressive symptoms.

- Target Brainwaves: Alpha waves (8-12 Hz) and Theta waves (4-8 Hz)

- Goal: Increase the amplitude of alpha and theta waves, particularly during relaxed wakefulness.

Procedure:

1. Electrode Placement: Place electrodes at Fp1 and Cz (reference).

2. Baseline Recording: Record baseline alpha and theta activity for 5-10 minutes.

3. Feedback Mechanism: Provide feedback through a calming visual (e.g., a serene landscape) or auditory (e.g., nature sounds) stimuli. Positive feedback occurs when alpha and theta amplitudes increase.

4. Training Sessions: Conduct 20-30 minutes of training sessions, 2-3 times per week, for 20-40 sessions.

5. Progress Monitoring: Use depression rating scales and follow-up qEEG to track progress.

Beta/SMR Training Protocol

This protocol focuses on increasing low beta (12-15 Hz) or sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) waves to enhance cognitive function and stabilize mood.

- Target Brainwaves: Beta waves (12-15 Hz)

- Goal: Increase low beta/SMR activity associated with calm focus and emotional stability.

Procedure:

1. Electrode Placement: Place electrodes at F3 (for left DLPFC) and Cz (reference).

2. Baseline Recording: Record baseline beta/SMR activity for 5-10 minutes.

3. Feedback Mechanism: Use visual (e.g., a moving object) or auditory (e.g., a musical tone) feedback. Positive feedback is provided when beta/SMR activity increases.

4. Training Sessions: Conduct 20-30 minutes of training sessions, 2-3 times per week, for 20-40 sessions.

5. Progress Monitoring: Utilize depression rating scales and follow-up qEEG to monitor changes.

High Beta Downtraining Protocol

This protocol aims to reduce high beta (18-30 Hz) activity, which is often associated with anxiety and reflective thinking in depression.

- Target Brainwaves: High beta waves (18-30 Hz)

- Goal: Decrease high beta activity to reduce anxiety and rumination.

Procedure:

1. Electrode Placement: Place electrodes at Fz (midline frontal) and Cz (reference).

2. Baseline Recording: Record baseline high beta activity for 5-10 minutes.

3. Feedback Mechanism: Use visual or auditory feedback. Negative feedback (e.g., screen dims, tone lowers) occurs when high beta activity is excessive, encouraging reduction.

4. Training Sessions: Conduct 20-30 minutes of training sessions, 2-3 times per week, for 20-40 sessions.

5. Progress Monitoring: Use depression and anxiety scales along with follow-up qEEG to track progress.

EFFECTIVENESS OF NEUROFEEDBACK FOR DEPRESSION

Neurofeedback for depression retrains the dysfunctional brain patterns associated with depression, making it a powerful treatment tool. With neurofeedback for depression, the brain practices healthier patterns of mood regulation. Sessions can range from twice to several times a week and average 30 minutes each.

Those with depression often notice improvement after only a few sessions, but for the brain to thoroughly learn to make healthier patterns consistently, several brain training sessions are required. With sufficient practice, the brain learns to make these healthy patterns and regulate mood independently.

Neurofeedback can help depression sufferers get their lives back. Your brain changes when you are depressed, and neurofeedback can help it relearn healthier patterns, giving those who suffer from depression a way out of the prison of their minds.

Before treatment

HAM (Hamilton Depression Scale)=28

HAS((Hamilton Anxiety Scale)=20

After treatment

HAM (Hamilton Depression Scale)=10

HAS((Hamilton Anxiety Scale)=8

The maps before treatment, shown in red in the first row, indicate significant overactivation in alpha and beta frequencies. The rating scale for depression (HAM) indicates severe depression, and the anxiety scale (HAS) indicates moderate severity. The post-treatment maps show that alpha and beta frequencies are no longer significantly elevated. The HAM score indicates mild depression, and the anxiety scale is within the normal range.

After neurofeedback for depression, about 77.8% of the patients made significant improvements during 1 year of follow-up, not only symptoms of depression but also anxiety, obsessive rumination, withdrawal, and introversion, while ego-strength has improved.

OTHER RECOMMENDATION HOW TO COPE WITH DEPRESSION

Reach out to other people. Isolation fuels depression, so reach out to friends and loved ones, even if you feel like being alone or don’t want to be a burden to others. The simple act of talking to someone face-to-face about how you think can be an enormous help. The person you speak to doesn’t have to be able to fix you. They need to be a good listener who’ll listen attentively without being distracted or judging you.

Get moving. When you’re depressed, just getting out of bed can seem daunting, let alone exercising. However, regular exercise can be as effective as antidepressant medication in countering the symptoms of depression. Take a short walk or put some music on and dance around. Start with small activities and build up from there.

Eat a mood-boosting diet. Reduce your intake of foods that can adversely affect your moods, such as caffeine, alcohol, trans fats, sugar, and refined carbs. Increase mood-enhancing nutrients, such as Omega-3 fatty acids.

Find ways to engage again with the world. Spend some time in nature, care for a pet, volunteer, and pick up a hobby you used to enjoy (or take up a new one). You won’t feel like it at first, but you will feel better as you participate in the world again.

FAQ: Neurofeedback for depression

Neurofeedback trains your brain to correct the abnormal electrical patterns and imbalances associated with depression. Using real-time EEG feedback, it teaches the brain to self-regulate, increasing activity in underactive areas (like the left frontal lobe) and calming overactive ones, leading to improved mood regulation.

Yes, research shows it is highly effective. Studies cited in the document indicate that neurofeedback can significantly reduce depressive symptoms. One result showed that 77.8% of patients made significant improvements that were sustained over a one-year follow-up period.

The most common protocols target specific brainwave imbalances. Key protocols include the Alpha Asymmetry Protocol (balancing activity between the brain’s hemispheres), Beta/SMR Training (increasing calm, focused attention in the left prefrontal cortex), and Alpha-Theta Training (promoting deep relaxation).

A typical course involves 20 to 40 sessions. Sessions are usually 20-30 minutes long, 2 to 3 times per week. Lasting change requires enough practice for the brain to learn and stabilize the new, healthier patterns.

Neurofeedback is a non-invasive, drug-free training method. The document states it produces no undesirable side effects. It does not involve electricity entering the brain; instead, it uses feedback to guide the brain toward self-regulation.

Unlike medication, which manages symptoms chemically, neurofeedback addresses the root cause by teaching the brain to correct its own dysfunctional patterns. This can lead to more lasting changes without the reliance on medication or its typical side effects, such as nausea, sleep disturbances, and sexual problems.

REFERENCES

Ribas VR, De Souza MV, Tulio VW, Pavan MD, Castagini GA, et al. (2017) Treatment of Depression with Quantitative Electroencephalography (QEEG) of the TQ-7 Neuro-feedback System Increases the Level of Attention of Patients. J Neurol Disord 5:340. doi:10.4172/2329-6895.1000340

Bruder et al., 2008 – Bruder, G. E., Sedoruk, J. P., Stewart, J. W., McGrath, P. J., Quitkin, F. M., & Tenke, C. E. (2008). Electroencephalographic alpha measures predict therapeutic response to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant: pre- and post-treatment findings. Biological Psychiatry, 63(12), 1171-1177. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.009

Wang, S. Y., Lin, I. M., Peper, E., Chen, Y. T., Tang, T. C., Yeh, Y. C., … & Chu, C. C. (2016). The efficacy of neurofeedback among patients with major depressive disorder: preliminary study. NeuroRegulation, 3(3), 127

Young, K. D., Siegle, G. J., Zotev, V., Phillips, R., Misaki, M., Yuan, H., Drevets, W. C., & Bodurka, J. (2017). A randomized clinical trial of real-time fMRI amygdala neurofeedback for major depressive disorder: Effects on symptoms and autobiographical memory recall. The American Journal of Psychiatry. Vol.174(8), pp. 748-755.)

Young, K. D., Siegle, G. J., Misaki, M., Zotev, V., Phillips, R., Drevets, W. C., & Bodurka, J. (2018). Altered task-based and resting-state amygdala functional connectivity following real-time fMRI amygdala neurofeedback training in major depressive disorder. Neuroimage: Clinical, 691-703. Doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.004

Cool website!

My name’s Eric, and I just found your site – biofeedback-neurofeedback-therapy.com – while surfing the net. You showed up at the top of the search results, so I checked you out. It looks like what you’re doing is pretty cool.

You took care of some points that I had not even thought about.

Your intensity of study is really extensive.

If you are going for finest contents like me, just pay a visit this site all the time because it offers feature contents,

thanks

That is very fascinating, You are a very skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your rss feed and stay up for in the hunt for extra of your wonderful post.

Also, I have shared your website in my social networks

Right away I am going away to do my breakfast, after having my breakfast coming again to read other news.

Hello! I really like your writing very so much!

percentage we keep up a correspondence more approximately your article on AOL?

I require an expert on this area to solve my problem.

May be that is you! Taking a look ahead to see you.

I read this paragraph completely regarding the resemblance of most recent and previous technologies, it’s amazing article.

Aw, this was a very good post. Taking the time and actual effort to generate a very good article.

I have been browsing online more than 3 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours.

It’s pretty worth enough for me. Personally, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you did, the internet will be much more useful than ever before.

Love your composing design– appealing and clear!

I blog quite often and I really appreciate your content. This article has really peaked my interest.

I’m going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information about once per week.

I subscribed to your Feed as well.

For the reason that the admin of this website is working, no doubt very quickly it will be renowned, due to its quality contents.

I have read so many articles concerning the blogger lovers however this post

is actually a fastidious piece of writing, keep it up.

We are a bunch of volunteers and starting a brand new scheme in our community.

Your site offered us with valuable info to work on. You’ve done an impressive activity and our entire neighborhood will probably be thankful to you.

Thanks for one’s marvelous posting! I seriously

enjoyed reading it, you will be a great author.I will be sure to bookmark your blog and

will eventually come back in the future. I want

to encourage you to ultimately continue your great work, have

a nice day!

Hello, I enjoy reading all of your post. I wanted to write a little comment

to support you.

I like how well-written and informative your content is. You have actually given us, your readers, brilliant information and not just filled up your blog with flowery texts like many blogs today do.

Hey! I am for the first time here. I came across this board and I in finding it really useful. It helped me out much. I am hoping

to give something again and aid others such as you helped me.

This post is packed with beneficial info, thanks for sharing!

I don’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post

was good. I don’t know who you are but definitely you are going to a famous blogger if you are not already. Cheers!

Just want to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is just cool and i can assume

you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab

your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

I like reading through a post that can make people think.

Also, thank you for permitting me to comment!

Thank you so much!

Thanks for the great article!