Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) presents a complex interplay of intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors, often disrupting daily life and causing significant distress. Traditional treatments, such as medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), are usually effective. However, some individuals experience only limited relief or face unwanted side effects. In recent years, a promising alternative has emerged: neurofeedback for OCD. This innovative approach taps into the brain’s incredible capacity to adapt and self-regulate. It offers renewed hope for individuals looking to break free from the persistent hold of OCD symptoms. In this exploration, we will dive into the world of neurofeedback therapy for OCD management. We will examine its core principles, practical applications, and its potential to reshape the future of OCD treatment.

Table of Contents

Toggle- What is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)?

- Pathological Changes in the Brain

- Traditional Treatments and Their Effectiveness

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP):

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs):

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS):

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS):

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions:

- Antipsychotic Medications:

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT):

- Neurofeedback Therapy for OCD:

- Introduction to Neurofeedback for OCD Treatment

- Neurofeedback therapy for OCD: Techniques and Protocols

- Neurofeedback for OCD: Benefits and Limitation

- List of References

What is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)?

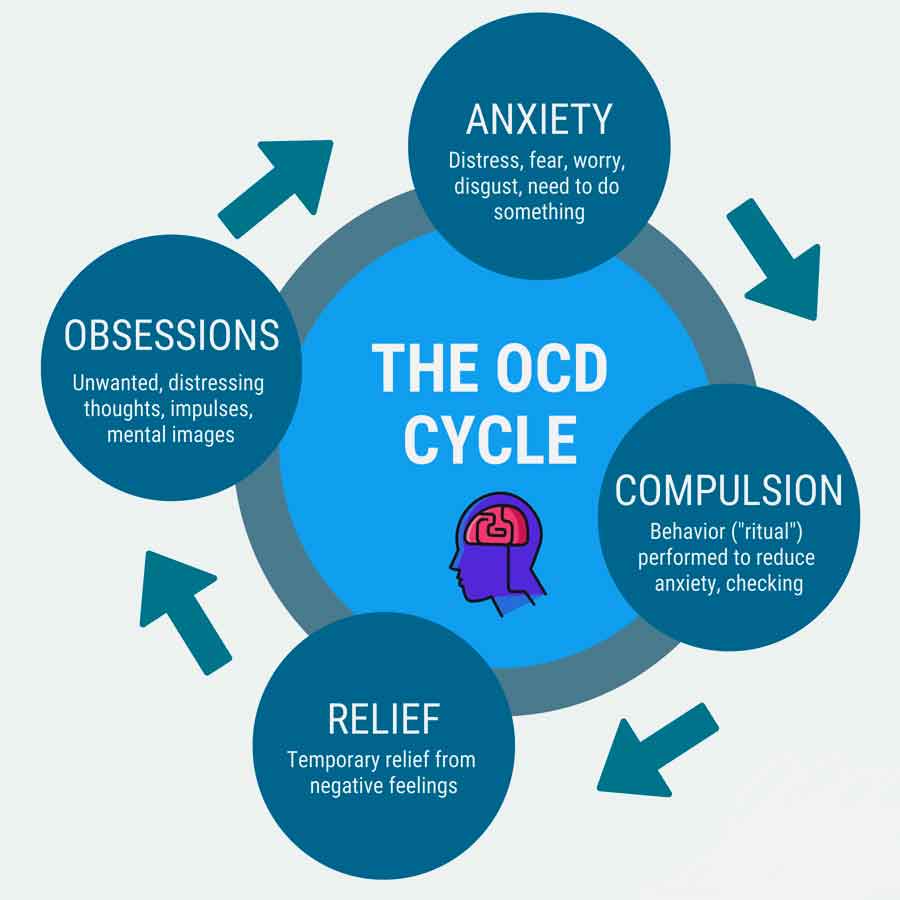

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a debilitating mental health condition characterized by a cycle of intrusive, distressing thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) performed in an attempt to alleviate anxiety or prevent a feared outcome. These obsessions and compulsions can significantly impair daily functioning, relationships, and overall quality of life for individuals affected by the disorder.

While 21 to 38% of individuals in the population endorse obsessions and compulsions, only a tiny minority meet the criteria for clinical OCD diagnosis. The lifetime prevalence of OCD is believed to be between 1% and 3%, and patients can experience chronic or episodic OCD symptoms throughout their lifetime. OCD is a time-consuming and distressing psychiatric disorder that has higher disability-adjusted years than Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis combined, making OCD one of the top 10 most disabling medical conditions. OCD is believed to diminish the quality of life of the patient, similar in extent to those individuals with schizophrenia.

Definition:

OCD is defined by the presence of obsessions, compulsions, or both. Obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges, or images that cause significant anxiety or distress. Compulsions, on the other hand, are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that an individual feels driven to perform in response to an obsession or according to rigid rules. While these compulsions may temporarily alleviate anxiety, they are not realistically connected to the situation they are meant to address.

Causes:

The exact causes of OCD are not fully understood, but a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors is believed to contribute to its development. Research suggests that abnormalities in neurotransmitter systems, particularly serotonin, may play a role in OCD. Additionally, structural and functional abnormalities in specific brain regions, including the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and striatum, have been implicated in the pathophysiology of OCD.

Symptoms:

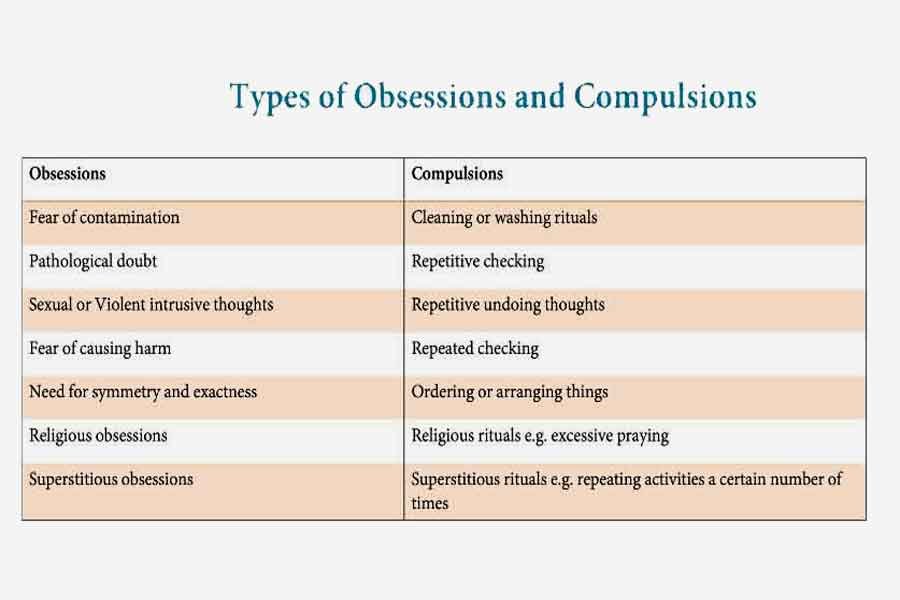

Symptoms of OCD can vary widely among individuals but often include intrusive thoughts related to contamination, harm, symmetry, or orderliness, as well as corresponding compulsive behaviors such as washing, checking, arranging, or counting. Other common symptoms may involve hoarding, repeating rituals, or seeking reassurance. These symptoms can lead to considerable distress, affecting many aspects of life. They often result in avoidance behaviors, making it hard to engage in everyday activities. This can create challenges in both social and professional environments, further impairing overall functioning.

OCD has three main elements:

- Obsessions – where an unwanted, intrusive, and often distressing thought, image, or urge repeatedly enters your mind

- Compulsions – repetitive behaviors or mental acts that a person with OCD feels driven to perform as a result of the anxiety and distress caused by the obsession

- Emotions – the obsession causes a feeling of intense anxiety or distress

The compulsive behavior temporarily relieves the anxiety, but the obsession and anxiety soon return, causing the cycle to begin again.

Most people with OCD experience both obsessive thoughts and compulsions, but one may be less evident than the other.

Some common obsessions that affect people with OCD include:

- fear of deliberately harming yourself or others – for example, fear you may attack someone else, such as your children

- fear of harming yourself or others by mistake – for example, fear you may set the house on fire by leaving the cooker on

- fear of contamination by disease, infection, or an unpleasant substance

- A need for symmetry or orderliness – for example, you may feel the need to ensure all the labels on the tins in your cupboard face the same way

You may have obsessive thoughts of a violent or sexual nature that you find repulsive or frightening. But they’re just thoughts, and having them does not mean you’ll act on them.

These thoughts are classed as OCD if they cause you distress or have an impact on the quality of your life.

Compulsions start as a way of trying to reduce or prevent anxiety caused by obsessive thought, although in reality, this behavior is either excessive or not realistically connected.

Common types of compulsive behavior in people with OCD include:

- cleaning and hand washing

- checking – such as checking doors are locked or that the gas is off

- counting

- ordering and arranging

- hoarding

- asking for reassurance

- repeating words in their head

- thinking “neutralizing” thoughts to counter the obsessive thoughts

- avoiding places and situations that could trigger obsessive thoughts

Most people with OCD realize that such compulsive behavior is irrational and makes no logical sense, but they cannot stop acting on it and feel they need to do it “just in case.”

Not all compulsive behaviors will be evident to other people.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Test & Self-Assessment

This quiz is NOT a diagnostic tool. Mental health disorders can only be diagnosed by licensed healthcare professionals.

Numerous inventories are currently available to clinicians to measure symptoms of OCD. The Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and the Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) are the two most commonly used measures.

The Y-BOCS is a semi-structured interview and consists of a checklist of common obsessions and compulsions and a 10-item measure of symptom severity, which determines symptom severity regardless of symptom subtype.

Total scores on the measure range from 0 to 40, with a score of

- 0–7 indicating subclinical symptoms,

- 8–15 mild symptoms,

- 16–23 moderate symptoms,

- 24–31 severe symptoms,

- 32–40 extreme symptoms.

Pathological Changes in the Brain

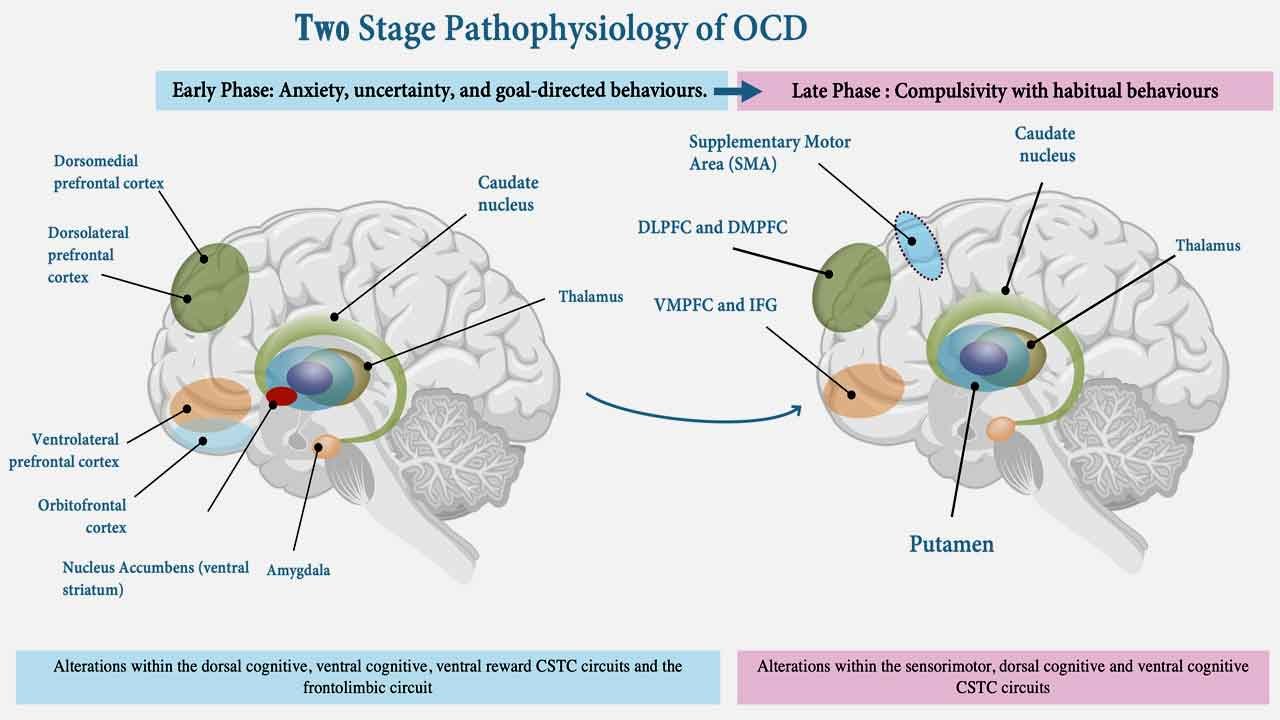

Neurochemical mechanism

The varying effects of serotonin-reuptake inhibitors on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) suggest that serotonin regulation plays a critical role in its pathophysiology. These differences are substantial enough to assume that a serotonin-regulatory disorder is a crucial factor in the development of OCD. In patients with OCD, however, a high dose of serotonin-reuptake inhibitor monotherapy may not be sufficient, and approximately half of patients were noted to be treatment-resistant.

Some studies show positive treatment responses to the dopaminergic antagonists. This suggests that other neurotransmitter systems, such as dopamine, are involved in the pathophysiology of OCD. Preclinical, neuroimaging, and neurochemical studies have provided evidence demonstrating that the dopaminergic system is involved in inducing or aggravating the symptoms that are indicative of OCD.

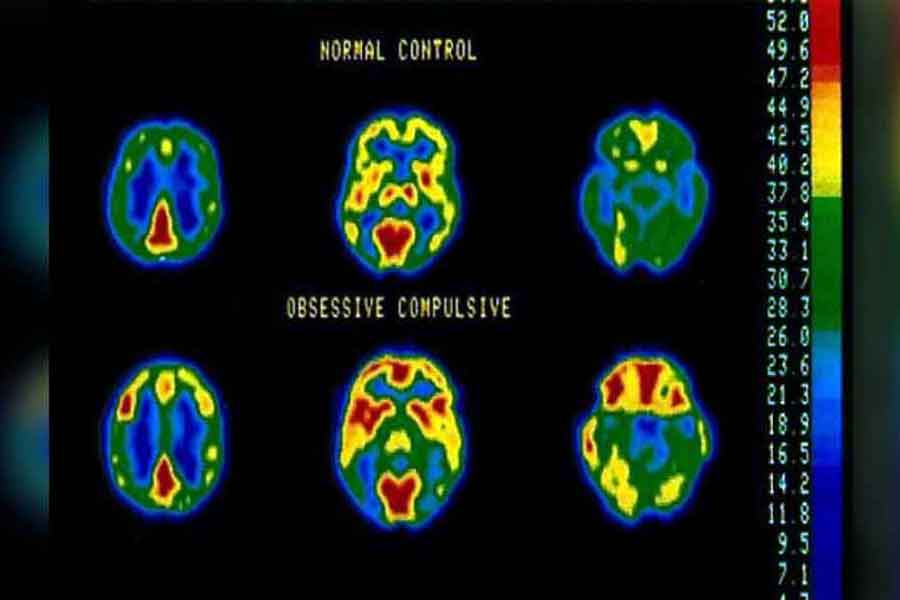

Structural mechanism

Neuroimaging studies have identified structural and functional abnormalities in the brains of individuals with OCD, particularly in regions involved in cognitive and emotional processing, such as the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and basal ganglia. These abnormalities are thought to contribute to the repetitive thoughts and behaviors characteristic of OCD.

The most widely accepted model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) assumes brain abnormalities in the “affective circuit,” mainly consisting of volume reduction in the medial orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, and temporolimbic cortices, and tissue expansion in the striatum and thalamus. The research found that OCD patients had smaller grey matter volume than health controls in the frontal eye fields, medial frontal gyrus, and anterior cingulate cortex. However, there was an increase in the grey matter volume in the lenticular nucleus, caudate nucleus, and a small region in the right superior parietal lobule. OCD patients also had a lower fractional anisotropy (FA) in the cingulum bundles, inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, and superior longitudinal fasciculus, while increased FA in the left uncinate fasciculus.

Traditional Treatments and Their Effectiveness

Traditional treatments for OCD typically include medication and psychotherapy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants are commonly prescribed drugs that help regulate serotonin levels in the brain and reduce the frequency and intensity of obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), particularly exposure and response prevention (ERP), is a type of psychotherapy that helps individuals confront their fears and reduce the urge to engage in compulsive rituals.

OCD treatment methods vary in approach, characteristics, and effectiveness, highlighting the importance of individualized treatment planning and considering patient preferences and treatment goals.

Here’s a list of OCD treatment methods along with their specifications, characteristics, and effectiveness based on literature data

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP):

- Specification: CBT with ERP involves exposing individuals to feared stimuli (exposure) while preventing them from engaging in compulsive behaviors (response prevention).

- Characteristics: Structured, evidence-based therapy focusing on changing dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors associated with OCD.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 60-80% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Side Effects: Minimal to none. The estimated incidence of adverse effects is less than 5%. Some individuals may experience temporary increases in anxiety or distress during exposure sessions.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs):

- Specification: SSRIs are a class of antidepressant medications that increase serotonin levels in the brain.

- Characteristics: Medication-based treatment targeting underlying neurotransmitter imbalances associated with OCD.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 40-60% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Side Effects: Common side effects include nausea, headache, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain. In some cases, SSRIs may increase anxiety or worsen depressive symptoms. Common side effects occur in approximately 20-30% of individuals. Severe side effects are rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS):

- Specification: DBS involves implanting electrodes in specific brain regions to modulate neural activity.

- Characteristics: Invasive procedure reserved for severe, treatment-resistant cases of OCD.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 60-70% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms in carefully selected patients.

- Side Effects: Potential surgical risks, including infection, bleeding, and damage to surrounding brain structures. Common side effects of stimulation may include transient mood changes, speech difficulties, or sensory disturbances. Surgical risks occur in less than 10% of cases. Common side effects of stimulation occur in approximately 20-30% of individuals, with severe side effects occurring in less than 5% of cases.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS):

- Specification: TMS uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain.

- Characteristics: Non-invasive procedure targeting specific brain regions implicated in OCD.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 30-40% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Side Effects: Common side effects include headache, scalp discomfort, and transient changes in hearing or vision. Rarely, TMS may trigger seizures in individuals with a predisposition to epilepsy. Common side effects occur in approximately 10-20% of individuals, with rare but severe side effects occurring in less than 5% of cases.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions:

- Specification: Mindfulness-based interventions involve cultivating present-moment awareness and acceptance.

- Characteristics: Non-invasive, skills-based approach focusing on developing mindfulness skills to manage OCD symptoms.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 30-40% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Side Effects: Minimal to none, with reported adverse effects occurring in less than 5% of cases. Some individuals may experience temporary increases in distress or emotional discomfort as they confront challenging thoughts or emotions.

Antipsychotic Medications:

- Specification: Antipsychotic medications may be used to augment SSRIs in severe cases of OCD.

- Characteristics: Medication-based treatment targeting psychotic symptoms and augmenting serotonin levels.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 20-30% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Side Effects: Common side effects include sedation, weight gain, metabolic changes, and movement disorders (e.g., tardive dyskinesia). Antipsychotics may also increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular complications. Common side effects occur in approximately 20-30% of individuals, while severe side effects occur in less than 5% of cases.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT):

- Specification: DBT combines cognitive-behavioral techniques with mindfulness-based strategies.

- Characteristics: Structured, skills-based therapy focusing on emotion regulation and interpersonal effectiveness.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 30-40% effectiveness in reducing OCD symptoms.

- Side Effects: Minimal to none, with reported adverse effects occurring in less than 5% of cases. Some individuals may experience temporary increases in emotional discomfort or distress as they learn new coping skills and strategies.

Neurofeedback Therapy for OCD:

- Specification: Neurofeedback therapy for OCD provides real-time feedback on brainwave activity to teach self-regulation of neural functioning.

- Characteristics: Personalized, non-invasive treatment targeting specific brain regions implicated in OCD symptoms.

- Effectiveness: Approximately 50-60% effectiveness in reducing obsession symptoms, 45-55% in lowering compulsion symptoms, and 40-50% in improving related behaviors.

- Side Effects: Generally considered safe and well-tolerated, with reported side effects occurring in less than 5% of cases. Rare side effects may include mild headache or fatigue during or after sessions.

While these treatments can be effective for many individuals with OCD, they may not work for everyone, and some individuals may experience only partial symptom relief or intolerable side effects. Therefore, there is a need for alternative or adjunctive treatments, such as neurofeedback, to address the diverse needs of individuals living with OCD.

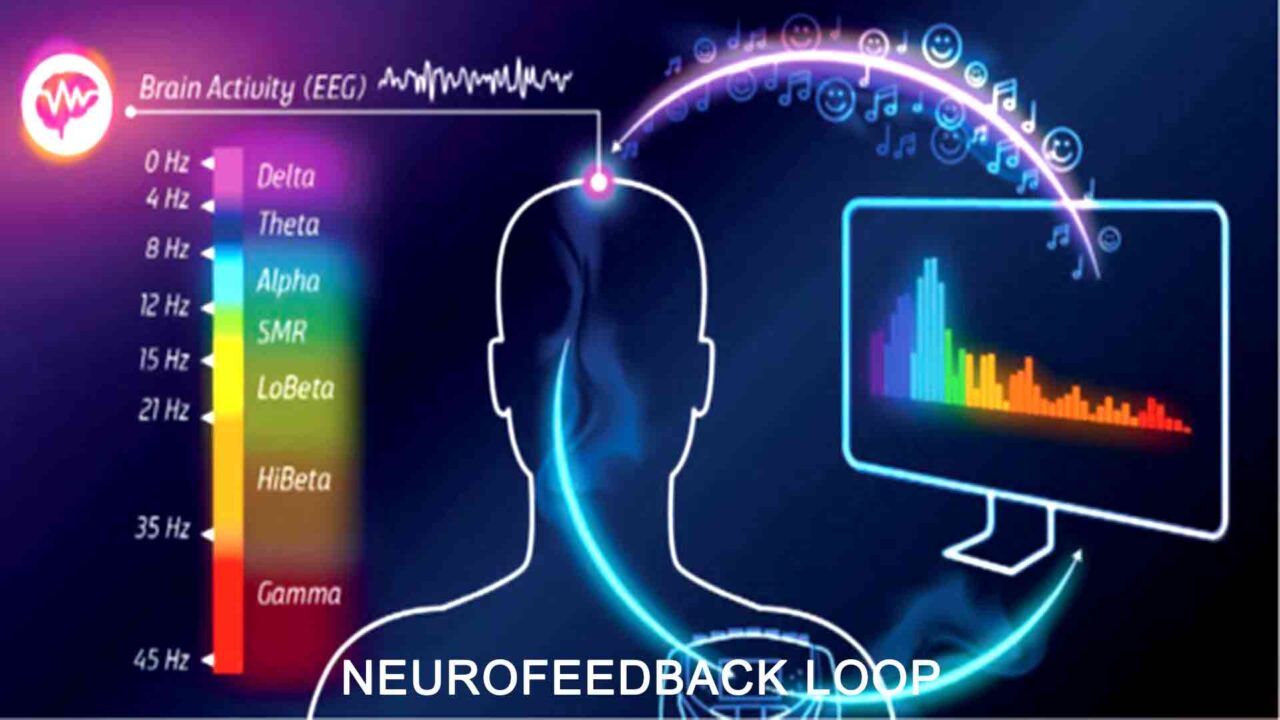

Introduction to Neurofeedback for OCD Treatment

In the realm of mental health interventions, qEEG-based neurofeedback for OCD emerges as a promising avenue, offering innovative approaches to symptom management and relief. Neurofeedback, also known as EEG biofeedback or neurotherapy, represents a non-invasive therapeutic technique that leverages real-time brainwave activity monitoring to empower individuals to self-regulate their brain function. The core principle underpinning neurofeedback is the brain’s inherent capacity for adaptation and learning, commonly called neuroplasticity. Individuals can actively learn to modulate their brainwave patterns towards more favorable states through feedback on brain activity, typically through visual or auditory cues.

At the heart of neurofeedback therapy for OCD lies a fundamental understanding of the disorder’s neural correlates and mechanisms. OCD is characterized by a dysregulation in brain circuits implicated in cognitive control, emotion regulation, and habitual behaviors. Key regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and striatum exhibit aberrant activity and connectivity patterns in individuals with OCD, contributing to the hallmark symptoms of obsessions and compulsions.

How Does Neurofeedback Work for OCD?

Neurofeedback entails individuals receiving real-time feedback on their brainwave activity, typically through visual or auditory cues, contingent upon achieving desired brainwave states associated with relaxation, focus, or emotional regulation. By repeatedly reinforcing these target states, individuals can learn to self-regulate their brain activity, fostering adaptive neural pathways and diminishing the intensity and frequency of OCD symptoms.

Moreover, neurofeedback therapy for OCD offers a personalized and non-invasive approach to OCD treatment, allowing for the customization of treatment protocols based on individual neurobiological profiles and symptom presentations. Through a series of neurofeedback sessions, individuals can gradually develop greater awareness and control over their brain activity, empowering them to manage their OCD symptoms more effectively.

Traditional treatments for OCD, including medication and psychotherapy, have demonstrated efficacy for many individuals, yet significant challenges remain, such as partial response, side effects, and treatment resistance.

Herein lies the allure of neurofeedback for OCD – its potential to offer personalized, targeted interventions that complement existing treatments and address treatment gaps.

In essence, neurofeedback therapy for OCD serves as a powerful tool in the arsenal of OCD treatment modalities, offering a tailored and innovative approach to symptom management. By harnessing the brain’s inherent capacity for adaptation and learning, neurofeedback allows individuals to take an active role in their recovery journey, fostering a sense of empowerment and control over their mental health.

Neurofeedback therapy for OCD: Techniques and Protocols

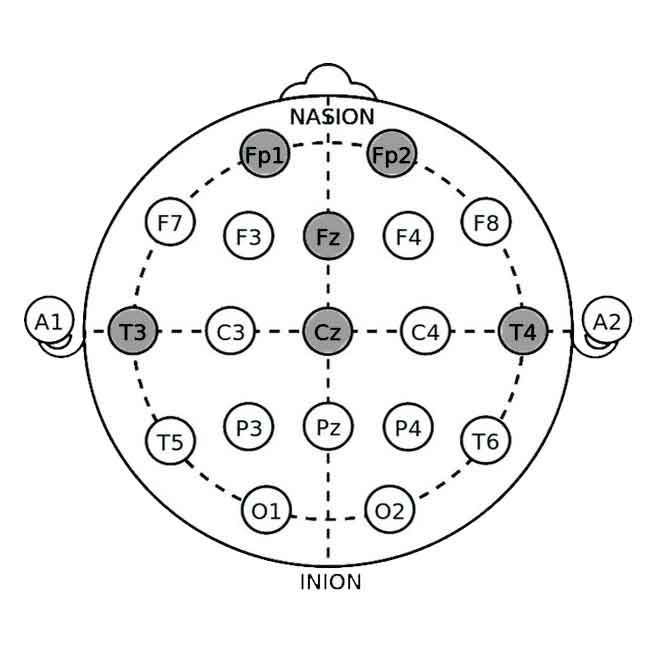

Electrode Placement Sites

The selection of electrode sites and neurofeedback protocols for OCD treatment should be based on a comprehensive assessment of the individual’s neurobiological profile, symptom severity, and treatment goals.

- Fp1/Fp2 (Frontopolar): Located at the frontal pole, these sites are associated with executive functioning, decision-making, and emotional regulation. Targeting these areas may help modulate cognitive control processes involved in OCD symptomatology.

- Fz (Frontal Midline): Positioned at the midline of the frontal lobe, Fz is involved in attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Training at this site may enhance cognitive control and reduce compulsive behaviors in individuals with OCD.

Target Frontal Sites (Fp1, Fp2, Fz) sites for protocols aimed at enhancing cognitive control, emotional regulation, and decision-making processes implicated in OCD.

- Cz (Central Midline): Positioned at the midline of the central region, Cz is involved in sensorimotor processing and self-regulation. Training at Cz may promote relaxation and inhibit hyperarousal states associated with OCD symptoms.

- Pz (Parietal Midline): Pz is involved in sensory integration and attentional processing at the midline of the parietal lobe. Training at Pz may enhance attentional focus and reduce rumination or intrusive thoughts in individuals with OCD.

- T3/T4 (Temporal): Located over the temporal lobes, T3 and T4 are involved in emotional processing and memory. Training at these sites may help regulate emotional reactivity and reduce anxiety or distress associated with OCD symptoms.

These electrode sites are selected based on their functional relevance to cognitive and emotional processes implicated in OCD. By targeting specific brain regions associated with symptom expression, neurofeedback can promote adaptive changes in neural functioning and alleviate the distressing symptoms of OCD.

Neurofeedback Protocols

Several neurofeedback protocols can be utilized to treat OCD, each targeting different aspects of neural functioning and symptom presentation. Choose neurofeedback protocols based on the individual’s specific symptom profile and treatment goals. For example, SMR training can enhance attention and cognitive flexibility, alpha-theta training can promote emotional processing and relaxation, and beta-training can improve cognitive control and reduce compulsive behaviors.

Sensorimotor Rhythm (SMR) Training:

One of the primary techniques used in neurofeedback for OCD is sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) training. SMR training involves reinforcing brainwave activity in the 12-15 Hz frequency range, typically over sensorimotor cortex regions (Cz, Pz). By promoting SMR activity, individuals can experience improvements in attention, relaxation, and cognitive functioning, which may help mitigate the symptoms of OCD.

Alpha-Theta Training:

Another neurofeedback technique commonly employed in OCD treatment is alpha-theta training. Alpha-theta training involves the reinforcement of brainwave activity in the alpha (8-12 Hz) and theta (4-8 Hz) frequency ranges, typically over central and occipital brain regions (Cz, Pz, O1, O2). This technique aims to promote states of deep relaxation and heightened awareness, facilitating emotional processing and the resolution of underlying psychological conflicts associated with OCD symptoms.

Beta Training:

This brainwave training involves reinforcing brainwave activity in the beta (15-30 Hz) frequency range, typically over frontal and central regions (F3, F4, Cz, C3, C4). Beta waves are associated with active concentration, alertness, and cognitive processing. This protocol aims to enhance focus, attention control, and mental flexibility, which may help reduce compulsive behaviors and intrusive thoughts in individuals with OCD.

SCP (Slow Cortical Potentials) Training:

SCP training typically involves electrode placement at central and parietal sites on the scalp (Cz, C3, C4, P3, P4), reinforcing slow cortical potentials and shifts in the brain’s electrical activity associated with cortical excitability and arousal level. This protocol aims to modulate cortical arousal and enhance self-regulation, promoting adaptive responses to OCD-related triggers and reducing compulsive behaviors.

These neurofeedback protocols can be tailored to the individual needs and symptom presentations of each OCD patient, offering a personalized approach to treatment that addresses the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of the disorder.

In addition to specific neurofeedback techniques, various protocols may be utilized to optimize treatment outcomes for individuals with OCD. These protocols often involve a series of neurofeedback sessions conducted over several weeks or months, during which individuals receive real-time feedback on their brainwave activity and learn to modulate their neural functioning.

In summary, neurofeedback techniques and protocols tailored for OCD treatment offer a promising avenue for individuals seeking relief from the debilitating symptoms of the disorder. By harnessing the brain’s inherent capacity for adaptation and learning, neurofeedback empowers individuals to take an active role in their recovery journey, fostering a sense of empowerment and control over their mental health.

Neurofeedback for OCD: Benefits and Limitation

Benefits

1. Non-Invasive and Drug-Free: Neurofeedback offers a non-invasive and drug-free alternative to traditional OCD treatments like medication, making it appealing to individuals who prefer naturalistic approaches or who experience intolerable side effects from medication.

2. Personalized Treatment: Neurofeedback allows individualized treatment protocols based on each patient’s unique neurobiological profile and symptom presentation. This personalized approach enhances treatment efficacy and may result in better outcomes than one-size-fits-all interventions.

3. Promotion of Self-Regulation: Neurofeedback empowers individuals to take an active role in their treatment by providing real-time feedback on their brainwave activity. Through repeated practice, individuals learn to self-regulate their neural functioning, fostering a sense of control over their OCD symptoms.

4. Potential for Long-Term Effects: Neurofeedback therapy for OCD has the potential to induce neuroplasticity changes in the brain, leading to lasting improvements in neural functioning and symptom relief. This may result in sustained benefits even after the completion of neurofeedback training.

Limitations

1. Limited Availability and Accessibility: Despite its potential benefits, neurofeedback therapy for OCD may not be widely available or accessible to all individuals with OCD due to factors such as cost, geographical location, and availability of trained practitioners.

2. Variable Treatment Response: The efficacy of neurofeedback for OCD can vary widely among individuals, with some experiencing significant symptom reduction while others may see minimal improvement. Factors such as severity of symptoms, comorbidities, and individual differences in neurobiology may influence treatment response.

3. Time and Commitment: Neurofeedback therapy for OCD typically requires a significant time commitment, lasting several weeks to months. Additionally, individuals may need to engage in regular practice outside sessions to maximize treatment benefits, requiring dedication and motivation.

4. Need for Further Research: While existing research on neurofeedback for OCD is promising, further well-designed studies are needed to establish its efficacy, optimal treatment protocols, and long-term effects. Additionally, more research is required to identify predictors of treatment response and factors that may influence treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, neurofeedback therapy for OCD offers a range of potential benefits for individuals with OCD, including non-invasiveness, personalized treatment, and promotion of self-regulation. However, it also has limitations such as limited availability, variable treatment response, and the need for further research. Despite these challenges, neurofeedback remains a promising avenue for OCD treatment, with the potential to improve symptom management and enhance the quality of life for individuals living with the disorder.

Furthermore, the integration of neurofeedback with other therapeutic modalities, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or mindfulness-based interventions, may enhance treatment efficacy and promote long-term symptom relief for individuals with OCD. By combining neurofeedback with evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches, clinicians can offer a comprehensive and holistic treatment approach that addresses both the neurobiological and psychological aspects of OCD.

Combining Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with neurofeedback therapy for OCD appears to enhance treatment effectiveness compared to monotherapy approaches. The combined treatment approach shows promising results in reducing obsession and compulsion symptoms, as well as improving related behaviors, with effectiveness rates ranging from 70-85%. Furthermore, the combined treatment is generally associated with minimal to no additional side effects, making it a favorable option for individuals seeking comprehensive and personalized OCD treatment.

List of References

- Abramowitz JS, Taylor S, McKay D. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8;374(9688):491-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60240-3. PMID: 19665647.

- Bralten, J., Widomska, J., Witte, W.D. et al. Shared genetic etiology between obsessive-compulsive disorder, obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the population, and insulin signaling. Transl Psychiatry 10, 121 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0793-y

- Goodman WK, Price LH, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;46(11):1006-11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. PMID: 2684084.

- Hammond, D. C. QEEG-guided neurofeedback in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Neurotherapy. 2003 7(2), 25-52.

- Hirschtritt ME, Bloch MH, Mathews CA. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1358–1367. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.2200

- Janardhan Reddy YC, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017 Jan;59(Suppl 1):S74-S90. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196976. PMID: 28216787; PMCID: PMC5310107.

- Lipton DM, Gonzales BJ, Citri A. Dorsal Striatal Circuits for Habits, Compulsions and Addictions. Front Syst Neurosci. 2019 Jul 18;13:28. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2019.00028. PMID: 31379523; PMCID: PMC6657020.

- Pittenger C, Kelmendi B, et al. Clinical treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005 Nov;2(11):34-43. PMID: 21120095; PMCID: PMC2993523.

- Pittenger, C, et al. Neurotransmitter Dysregulation in OCD. Obsessive-compulsive Disorder: Phenomenology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. New York, 2017; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Oct. 2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190228163.003.0025

- Rance M, Zhao Z, et al. Neurofeedback for obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomized, double-blind trial. Psychiatry Res. 2023 Oct;328:115458. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115458. Epub 2023 Sep 3. PMID: 37722238; PMCID: PMC10695074.

- Sürmeli T, Ertem A. Obsessive compulsive disorder and the efficacy of qEEG-guided neurofeedback treatment: a case series. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2011 Jul;42(3):195-201. doi: 10.1177/155005941104200310. PMID: 21870473.

- Stein DJ, Costa DLC, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Aug 1;5(1):52. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0102-3. PMID: 31371720; PMCID: PMC7370844.

It’s hard to come by experienced people for this subject, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about!

It’s hard to come by experienced people for this subject, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks